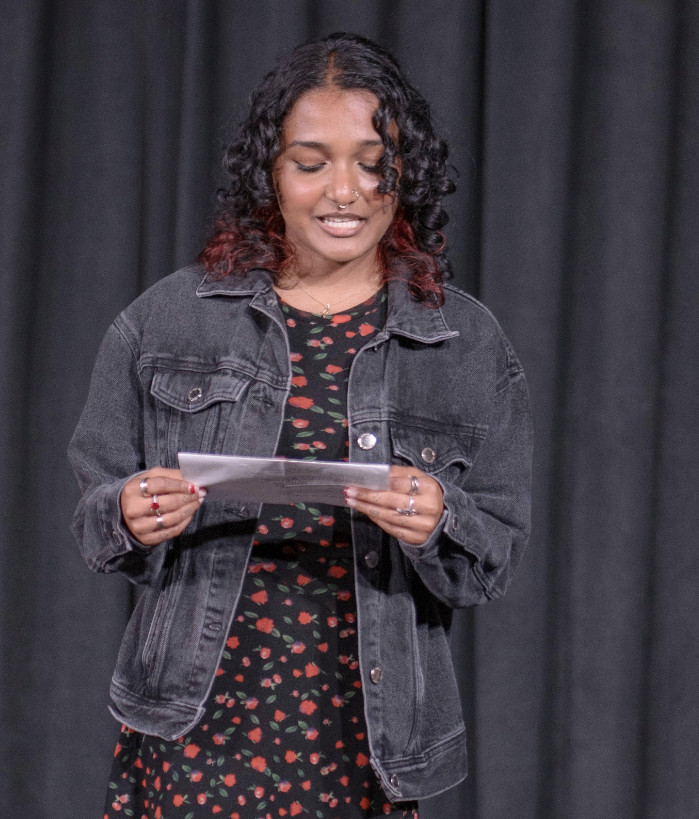

Writing from the Wound: Resh Grewal

For young writers, the advice is often “write what you know.” And so, the question becomes: What do I know?

In many ways, this may be a question that young people seek to avoid. In painful periods of self-growth and in mundane life trials – your chemistry pop quizzes and the like – what you know and of course what you don’t know can be an area of discomfort. Resh Grewal knows this intimately.

The 22-year-old and recent graduate of UCSB is a developing writer and life-long lover of stories. Born in India, Resh has spent the last four years at UCSB wading through the choice between self-expression and self-concealment. Today, they have joined us in the column to talk about their journey into writing.

Dear Montecito,

I found solace in books at a young age. My local library was an ivory tower, holding bits of beauty and worlds that I could submerge myself into. Reading is a form of escapism for many people, and for me it was also a part of survival. During this time, I also dabbled in writing. I experimented with different forms, writing songs and short stories inspired by nature and the people around me. But I was careful not to write about myself. I didn’t think I was grand like the people in the picture books and novels were, I didn’t think I earned a role beyond the narrator.

I wrote my first book in sixth grade, kind of as a dare to myself. A test. I ended up with six hundred and sixty-seven pages handwritten. There were plot holes and underdeveloped characters, but it was a new world. One of my own creation. My wrists hated me, but my heart felt full for the first time. The day that I blissfully wrote ‘the end’ and closed my fifth notebook is the day I decided I would pursue writing. I needed to. I had not just proven to myself that it was possible, that I was passionate enough to dedicate endless hours to narrative prose, but I honestly felt like it was meant for me.

Surrounded by notebooks with ink-stained fingerprints is when I felt understood. I had the power to distort time and travel through it, explore different characters and let them help me understand the world around me. Throughout middle and high school, I continually completed notebooks, wrote for hours on Word docs, hiding and finding pieces of myself in the narratives, still believing I didn’t deserve an audience’s gaze. I even began putting writing online anonymously, gaining a good following and getting hundreds of thousands of reads. It was motivating, interacting with people from around the world who found something of value in the words I tangled together.

From the age of 12, college was my goal, and I knew writing was my ticket in. I thought of college as a sort of savior. In the ways that reading and writing provided mental escapes, college would allow for a physical one. I love my family, but there was also a chaos that I needed to get away from. I was worried that I would never be able to find myself, or define myself, as separate from them, unless I created physical distance. During my junior year of high school, I found the College of Creative Studies at UC Santa Barbara. The intellectual autonomy is what overall drew me in, but the creativity, absurdity, and community that it fostered made me fall in love.

I committed to CCS with the sole intention of writing realistic fiction. Because of the adversities I had experienced and witnessed throughout childhood, I had a special interest in human psyche and psychopathology. Intergenerational trauma, mental illness, development, and identity were all common themes in my work. I stubbornly didn’t want to admit why. Many of us write what is familiar to us, even if we want to face that or not, and I hid artifacts of myself in the characters and plots that I developed.

When assigned to write a creative nonfiction piece for a required class, I struggled a bit, unfamiliar with being so honest. So, I did what I did best, I hid. I wrote a story about my cat, her life and her trauma, her anxiety and her journey to finding peace, using her to mirror myself. In response to my submission, I was told to write a memoir, which I abrasively rejected. At least ten professors and mentors voiced similar sentiments, encouraging or directly telling me to write one. My second year of college, when proposing my Senior Capstone project, I caved, proposing a collection of personal essays.

I never thought of myself as a main character, but I appreciate stories. And I appreciate the things stories do. I always understood my stories as an interrogation of the binary, an exploration of gray areas. I want to disrupt the common, romanticize the mundane, dive in deep into shadows. When I began this collection, I wrote about a plethora of experiences, topics that I felt were neglected or misrepresented: when food becomes a weapon, when affection becomes a demand, when love becomes confused with fear.

I wrote nonlinearly, with the intention of my collection to be unchronological. To connect the pieces, I began writing poems and open letters to aid the essays. Soon there was a common thread, a continuation of open letters to my deceased mom, who I lost way too young and whose death I never truly processed until I was faced with the challenge of writing about my life.

I realized eight months into the writing process that this memoir wasn’t about creating a narrative of my life. It wasn’t really about me at all. It was about her, and it was for her. It’s an exploration of grief and love. Writing from the wound and writing from the care I have for my mom, honoring her and sharing my life with her, and in that, sharing her life with you, the reader. Writing isn’t confined by the laws of nature, it’s not dictated by life or death. I think that’s the beauty of it, that’s what drew me in all those years ago. As I completed my memoir for my Senior Capstone Project and for the Raab Writing Fellowship this past year, I began to understand writing as more than storytelling. Writing is resurrection, writing is immortalization, but most importantly, writing is transmutation.

Yours,

Resh Grewal