‘Diving Deep’ into deGruy’s Degree of Influence

Nearly nine years after his death, prolific Montecito underwater filmmaker Mike deGruy’s world comes back to life via Diving Deep: The Life and Times of Mike deGruy, the documentary written and directed by his wife and filmmaking partner Mimi Armstrong deGruy. The film doesn’t only cover his underwater life, where deGruy most assuredly blew past typical seafarer boundaries to explore the ocean’s depths and visit the creatures who live there as Diving Deep also delves into Mike’s motivations, his youth, his passion for the environment, and – most touchingly – his family life in Montecito.

The bulk of the film features deGruy’s captivating underwater cinematography balanced by his often humorously self-deprecating on-camera commentary, plus plenty of accolades from his former colleagues that include Academy Award-winning filmmaker James Cameron, for whom deGruy was shooting when a helicopter crash took his life in Australia in February 2012.

But some of the most moving as well as lighthearted moments come from the deGruy children, son Max and daughter Frances, who were just 18 and 14, respectively, when Mike died. But both had already served as assistants on some of Mike’s projects and, later, aided Mimi in producing the documentary about their dad that includes scenes of them playing as infants.

Diving Deep premiered by opening the 2019 Santa Barbara International Film Festival – we ran an extensive interview with Mimi at the time – before going on to claim multiple awards on the film festival circuit, including Best Film at the Ocean Film Festival and Audience Favorite at the Aspen Mountain Film Festival. In early 2020, the film had a limited theatrical release, opening in 35 cities, before the pandemic canceled more screenings.

Now, two years after it first screened in town, the film is set to make its streaming debut via Apple TV/iTunes and Amazon Prime Rentals on January 19.

We caught up with Mimi, Max, and Frances via Zoom last weekend. Here are excerpts from the conversation.

Q. Mimi told me two years ago that beginning to work on the documentary less than a year after Mike died was stressful but also healing. Max and Frances, you were involved, too. How was it for you?

A. Frances: It was a very emotional process for all of us to go in and see it during the early stages of development and kind of try and help weed out which clips should be in it and which were too personal. We mostly acted as sounding boards for our mom and mostly I was thinking that what she was doing was amazing: it’s hard, but it’s going to be worth it.

Max: My mom was such a trooper going through all of that stuff, looking through the footage of my dad after having not seen it for so long right after we lost him. I can’t imagine how hard that would have been to do it by herself. So I’m glad that we could be a little bit of a support mechanism for my mom, but also help decide what was important and what was too close to home. And then of course we were interviewed too.

Mimi, I still can’t imagine anything harder than trying to be a filmmaker while looking at the footage is also hitting your heart nonstop just months after he was killed. I know we talked about this before, but how did you get through that?

Mimi: There were a couple of reasons I had to make the film. The first was that I felt Mike had a lot more to say, but he was cut short, and I wanted to do my best to imagine where he would’ve gone. But it was also part of the grieving process for me, like I was continuing my conversation with him and that he was present while I worked on it. So it was an incredible gift to be able to do it.

In the movie, Mimi talks about hearing the news of Mike’s death and thinking “How can someone so full of life be here one minute and then gone the next?” The film doesn’t have anything about the kids’ reactions. I don’t want to pry, but can you talk about what it was like?

Max: Going back to that night’s pretty tough. But I can say that he was a rock, always a constant in my life, so it was a given that he would always be there and be a support mechanism. To have that gone so suddenly shook my faith in everything because I had taken his presence for granted. If we can relate that to the movie, I think we often take the natural world around us for granted. We expect it to always be there, to be in the same shape or form that we know it, but when it is gone, there’s no getting it back either. So we have to protect it.

How is it for you to have those little pieces of home movies in there? How were those choices made?

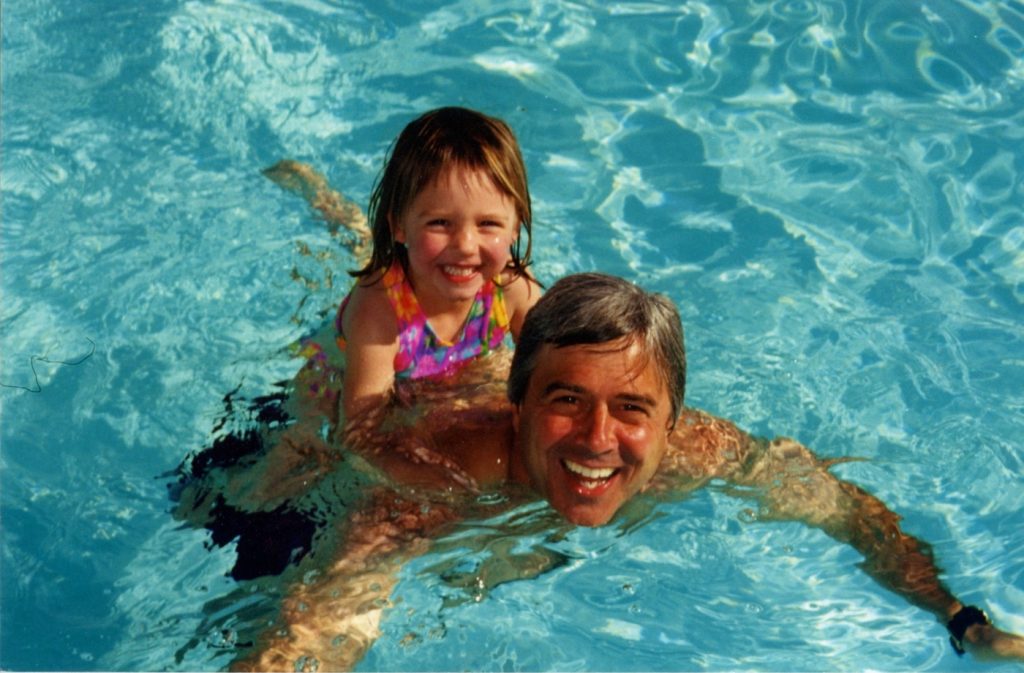

Max: The decision making really came down to my mom, but we had veto power. I think it adds to the movie. It shows that my dad tried to expose us to as much of the outdoors as he could all throughout our lives. I mean, I’ve got the hummingbird on my head when I was an infant. So I think it adds a lot of characterization for him and shows our family in a pretty realistic light.

Frances: The first time I saw the finished product was when it premiered at SBIFF, which was weird because I was looking around and thinking, that’s baby pictures of me and my brother screening for this huge audience (at the Arlington Theatre). But it was very accurate of what growing up was like, because we did have our lives so intertwined with the natural world. Our dad would go off on these expeditions, but because he was a self-employed freelance cinematographer, much of what we did in normal day-to-day life was also kind of combined with work. There wasn’t really a big separation between the two. We’d go camping, but it was also an opportunity to film, whether that was Max and I running around or filming the squirrels and the birds. Even sitting at the dinner table, there would be a camera in your face. There’s a clip that didn’t make it in the movie of my dad asking me what I think about dolphins living underwater but breathing on the surface. I was six years old but he was trying to get a complex interview with my childhood views of the natural world. That was just a normal table conversation. So home life and work life were all really mashed up together.

Later, though, I remember getting my first camera as a Christmas gift when I was 10 and there was never any hesitation to let me take pictures of anything. If we were driving down the street, we could pull over at any point and get out on the side of the road and both of my parents would be so patient when I’d be on the ground taking close-up pictures of grass that would probably be deleted a couple of days later. There was a lot of room for our own creativity.

I’m realizing that neither of you has mentioned filmmaking or working specifically with nature as anything you’re doing professionally or otherwise currently. Has that been a conscious choice not to take up the family business?

Frances: On paper it does seem like we’ve really gone in different directions, but for me it doesn’t feel that way. Both parents always told us that it doesn’t really matter what you do, but whatever you choose, be passionate about it, be really involved, and get really in with the community. That was really ingrained in us. And that’s what I’ve done with healthcare, where for me that sense of community is really important. And Max and I were scuba divers growing up and have been really involved in the ocean. That sense of love and respect and relationship will always be there. The ocean and diving will always be a really important part of my life even as I’ve explored other facets and gotten involved in other things.

Max: For me, when I went away to college, I was at a stage of life where I wanted to branch out from my dad a little bit. I had gone to Santa Barbara High School and participated in the multimedia arts and design academy, where I learned a lot about camera work and editing. I participated in the 10-10-10 student film project with SBIFF and was immersed in all of the film lifestyle. But I wanted to branch out at college and maybe return to it later. Then when my dad passed in my freshman year, subconsciously I needed to just distance myself from all of it. I think it was a bit too close emotionally to him to be able to pursue that at the time. So I studied English and writing and storytelling, which is actually what my dad was, too. But the outdoors and film are coming back into my daily life. We’ll see where we go. I think time will tell, but I wouldn’t expect film to be too far from either of our lifestyles.

Mimi: I just want to pipe up for one second. I know what they said is true, but I also think the jury is still out, at least with Max. He has encyclopedic knowledge of film. (To Max): You’ve seen more movies than anyone I know your age. So I’m just sitting back watching this movie unfold with both these kids.

Now that the film is being released to the general public, is it tough for you to watch it? Is it fun? Healing? Or maybe something else?

Frances: All of the above. It’s increasingly less difficult to watch and more really fun, especially when I show it to other people, because the reaction overwhelmingly at the end is that it makes you analyze your own life a little bit. What kind of impact have you made? What kind of impact do you want to make? What sorts of communities will really matter to you and how can you make a big contribution to that? My hope is that you look at the natural world a little bit differently after watching it. I always feel excited because like Max said it does totally feel like we get to hang out with our dad for an hour and a half again, which is really rare and special. And I still can’t quite wrap my head around (what happened). But I think that that sense of being reinvigorated, passionate, and excited is really contagious.

Max: I’d agree. Once you finish that movie, you just want to start something immediately. You want to get out there and fix things. One of the final memories I have of my dad was around the time of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, with him being so depressed and disappointed at the reactions (where people didn’t seem very concerned about) the implications and effects for the wildlife around it that were so great and so tragic. I think he was curious why we weren’t focused more on that. So it’s a healing experience just to know that his message will be given to many people. He was still trying to figure out how to get that message out (when he died). So thank goodness for my mom for finalizing that idea and those words. Thanks, mom.