Riding the Rails in Idaho

In mid-September, my husband Michael and I hit the road and traveled to Kellogg, Idaho, to ride the rails. Our locomotion, however, was pedal-powered and the iron rails had long been torn out, leaving behind two rail corridors: one of the Union Pacific Railroad and the other of the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific Railway (more commonly known as the Milwaukee Road). Thanks to the efforts of the Rails-to-Trails Conservancy, these former railways are now open to the public for hiking and biking.

The first, the Route of the Hiawatha, begins at St. Paul Pass Tunnel in the Bitterroot Mountains near Lookout Pass and Montana. It is named for the 1947 luxurious passenger train, which itself was named after Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s hero who was so fleet of foot he could outrun an arrow. Though far from the shores of Gitche Gumee, the Olympian Hiawatha could reach speeds of 100 miles per hour and was the pride of the Milwaukee line.

Wanting to expand its market westward to take advantage of the expanding trade on the Pacific coast, the Milwaukee company hired surveyors in 1904 and commenced building in 1907. A babble of 9,000 immigrant laborers assembled in makeshift towns, complete with saloons and brothels. Shifts worked day or night all year long to build the original wooden trestles and dig out the tunnels. Wages averaged $1 a day, and the tunnels were dug with pickaxes and shovels.

In 1910, a forest fire broke out and grew into an inferno that consumed 2.5 to 3 million acres. A massive cloud of smoke spread eastward as far as the St. Lawrence Seaway and Watertown, New York, where the skies were so dark, lamps had to be lit during the daytime. Many rail workers were rescued when a brave engineer drove the train into the conflagration and brought a large group of workers to the longest tunnel to sit out the fire, before setting off again to rescue others.

The Route of the Hiawatha begins at the Taft (aka St. Paul Pass) Tunnel, which is 1.66 miles long. Trail docents wisely check to make sure cyclists have two sources of light. No matter the heat of the day, the tunnel maintains a steady temperature of 47 degrees. And it’s dark. Very dark. And damp. A constant echoing drip of water accompanies the riders through the abyss. The headlamps only illuminate a few feet ahead and there’s no point of light to steer toward for the longest time. It’s very spooky, and very fun.

Railway grades being what they are (1 to 2.2%), the dirt trail runs steadily and gently downhill through a beautiful 111-year-old forest, through nine more tunnels and over seven sky-high iron trestles. Along the way the tales of the railroad and the fire are told through fascinating interpretive signboards. Fifteen miles later the route ends, and some riders return the way they came. Most, however, like we, have paid for the shuttle bus, which brings bikes and riders back to the top via a separate road.

The Trail of the Coeur d’Alenes

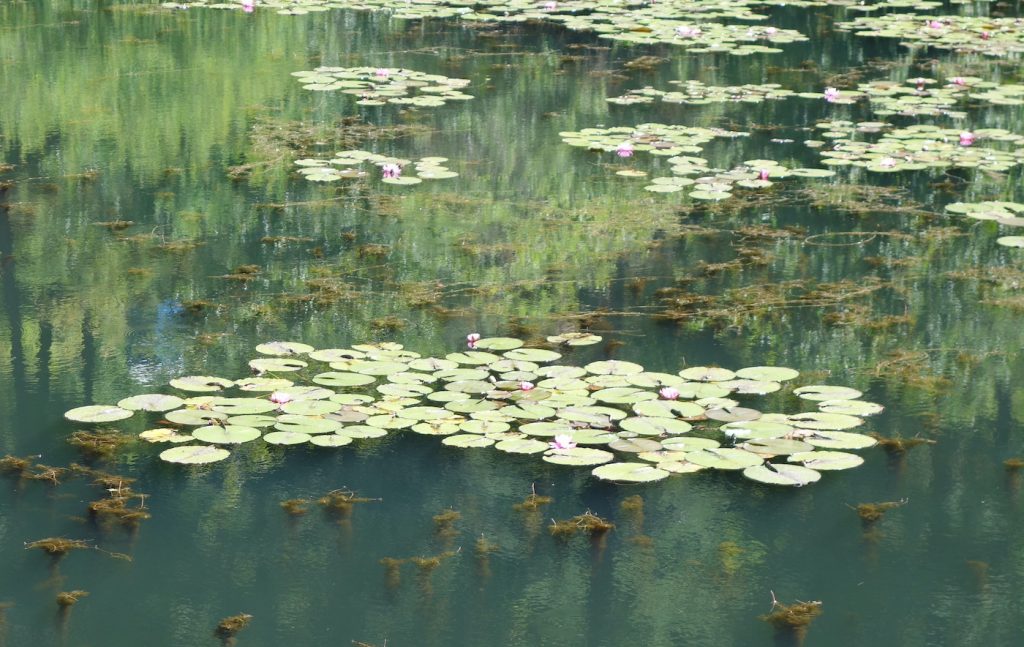

The next day, the crunch of autumn leaves and the snap of pine needles accompanied the gentle rush of the river as we rode the Trail of the Coeur d’Alenes, the route of the Wallace Branch of the Union Pacific Railroad. Yellow warblers and song sparrows added their voices to the concert while baby osprey contributed a piercing counterpoint. Moose grazed in the shallows of the river, and islands of beaver dams rose from the water lilies of the ponds.

Inducted into the Rail Trail Hall of Fame in 2010, the 73.2 miles long trail wends its way along the shores of the river and its many lakes, often straddling both, as well as several mining towns. Starting out in Plummer, Idaho, it terminates near Mullin near Lookout Pass on Highway 90 near the border of Montana.

Back in the day, more than 100 years of mining enterprises had dumped 72 miles of waste into the Coeur d’Alene watershed. In 1991, the Coeur d’Alene Tribal Council led a lawsuit to force the restoration of this watershed, and by 1993, the Union Pacific had abandoned its floundering Wallace Branch. The fill for the rail consisted of mine tailings rife with hazardous chemicals used in processing silver, lead, and zinc.

About that time, the newly formed Rails-to-Trails organization began working with trail advocates and various governmental agencies to rehabilitate the old railway for a bicycle and hiking trail. That they chose to cap the polluted rail bed with asphalt was a true boon to cyclists. The Trail of the Coeur d’Alenes officially opened in 2004 and has provided a beautiful transportation and recreational corridor for millions of people in the intervening years. Like rail trails elsewhere, it has supported a new and vibrant economic base for the Silver Valley.

The eastern portion of the trail traverses the Silver Valley with its old mining towns. One of the largest and most intact of these towns is Wallace, which was founded in 1884 and became the regional center for silver mining in the area. Today, Wallace is on the National Register of Historic Places. Its well-preserved Victorian-era brick buildings mainly house an interesting assortment of eating and drinking establishments, but Wallace also has a sense of humor and around each corner lie eclectic surprises.

The trail, which is completely off the road and meanders over trestles and through woods and along farmland, passes through many of these old mining towns including Silverton, Osburn, Kellogg (which has become a ski resort), Smelterville, Enaville, and Cataldo. From Cataldo, a detour of three miles on a quiet auto road leads to the Cataldo Mission. It was founded in the early 1850s by Jesuit missionaries and constructed by the Coeur d’Alene peoples. They called themselves the Schitsu’umsh, meaning “discovered people” or “those who were found here.” French fur traders, however, referred to the tribe as the Coeur d’Alene for their exceptional trading skills, which were sharp as the heart of an awl.

West of Kellogg, the landscape widens and the trail meanders through pine forest and along the river until it crosses under Highway 90 to straddle the waterlands and the river. In July, mile after mile of pink water lilies cover the ponds in impressionist splendor, Monet’s Giverny Idaho-style. Bald eagles nest in the tall pines, verdant mountains reflect in the quiet waters, and wildflowers line the trail. In early fall, verdancy hangs on tenaciously in the willows, cottonwoods, and aspen, but golden tones begin to highlight the countryside.

The trail passes through the historic town of Harrison, at the mouth of the Coeur d’Alene River. Over the years the town experienced a gold rush and a timber boom eventually becoming a landing for steamboats and a stop for the railroad. Today it is the sole town on this section of the trail and offers food and drink to both trail riders and boaters, who explore the many lakes attached to the river upstream. Farther along, the trail crosses the Chatcolet swing bridge whose central portion has been raised to allow for boat travel and affords wonderful views.

Rails-to-Trails Conservancy

We spent four days riding the rails and added 100 miles to our odometers. Not much, really, when you consider how easy the riding is. In fact, some people would do that mileage in a day. But there’s so much to see and appreciate, such great little picnic areas along the way, so many photos to take, such interesting interpretive signs, such lovely little towns and museums to explore — so why would we?

With 20 developed trailheads along the way, great maps, and excellent instructions, it was easy to choose an up-and-back route for each day. And all of this is thanks to the Rails-to-Trails Conservancy and Idaho State Parks and Recreation. When the conservancy first formed in 1986, there were 250 miles of rail trail in the United States. In 2021, there are more than 24,000 miles of trail. (Locally, the Ventura and Ojai bicycle trails — which connect to each another — are rail trails.) Working with local, state, and national groups and authorities, the Conservancy hopes to help develop additional mileage, and is especially working to create the Great American Rail-Trail, which will seamlessly link the nation from east to west.

Enough words. The photos tell it all!

(Sources: https://familyrvingmag.com/2012/10/01/ride-the-route-of-the-hi awatha/ Ride the Route of the Hiawatha, by Denise Seith, October 2012; www.ride thehiawatha.com/history; Rails-to-Trails Conservancy website; Trail of the Coeur d’Alenes website; Cataldo Mission information boards and docents.)

You must be logged in to post a comment.