What Chard Wrought

In the 1920s, American Santa Barbarans, enthralled with the mystique of Santa Barbara’s romantic Spanish past, set about preserving the rapidly-disappearing adobes. Ester Hammond purchased and paid for the preservation of the Hill/Carrillo Adobe, architect Louise McVhay completely renovated the Gonzalez/Ramirez adobe to reflect her vision of a romantic ranch house, and Irene and Bernhard Hoffmann preserved the De la Guerra Adobe while creating a charming faux Mexican village known today as El Paseo. They also preserved the Lugo adobe, but like McVhay, “improved” its architecture to reflect a fictious vision of the past.

Into this mix, came architect John William Chard, a descendent of a pioneering California family. Chard’s grandfather, New York born William George Chard, had traveled the Santa Fe Trail to arrive in Los Angeles in company with other trappers and traders in 1832-33. With a partner he established a soap factory and vineyard on the San Gabriel River before moving north in 1837 to try his luck in Santa Barbara. For a short time, he worked as a trader and otter hunter on the coast, and stayed in the Channel City long enough to become a naturalized Mexican citizen before moving on to Santa Cruz.

On December 3, 1839, he converted to Catholicism and was baptized at Mission Carmel as “Jorge Guillermo Chard.” One month later he married the young Maria Estefana Robles at Santa Cruz. In 1844, Chard received a Mexican land grant of some 13,000 acres in Tehama County on the western bank of the Sacramento River. He named it Rancho de las Flores and constructed a log cabin, which he called “Sacramento House.” In 1857, fire destroyed the dwelling and Maria almost died. Vaqueros on the ranch had to chop a hole in the wall to get her out. Valuable papers were burned as well as cherished relics of the days of Spain. When they rebuilt, they rebuilt with tried-and-true fireproof Mexican adobe.

Maria and William’s first-born son, Joseph William Chard, was born in 1841. As he grew up, Joseph ran stock and farmed on the family’s ranch in Tehama, but by 1879 he had moved to Montecito and found work as a butcher. In 1880, he married Dina Garcia, and they moved onto a portion of the 1820 Garcia family land grant in Montecito’s Cold Spring Canyon. John William Chard, born the following year, was their first child. Ten would follow.

Though several of their children were born at the homestead in the canyon, Dina, was deathly afraid of rattlesnakes and feared that one of her children might be bitten in this viperous environment. By 1894, she apparently had said “enough,” and the family moved to Carrillo Street in town and later to 1129 San Pascual Street.

The Adobe Architect

About 1904, the eldest son, John William Chard, headed for San Francisco where he joined his brother Alonzo and other Chard relatives in working for Shreve & Co, a silversmithing firm. By 1915, he had become an architect, most likely through an apprenticeship. He returned to Santa Barbara, moved in with the family at 1129 San Pascual, and built himself an apartment attached to the garage, where he spent his days drawing architectural designs. He also threw himself into the civic life of the town and became involved with the Hikers, the Progressive Business Club, Neighborhood House, and other organizations.

A native son of California with both Spanish and American heritage, Chard had probably heard the story of his grandmother’s near immolation on Rancho de las Flores and the conflagration that took his Uncle Stephen’s house in Red Bluff. His own family had lived in an adobe house in Cold Spring Canyon, so it is no wonder that Chard’s architectural specialty turned to the reintroduction of adobe bricks as a viable building medium. By 1916, he was already being referred to as “the adobe architect.”

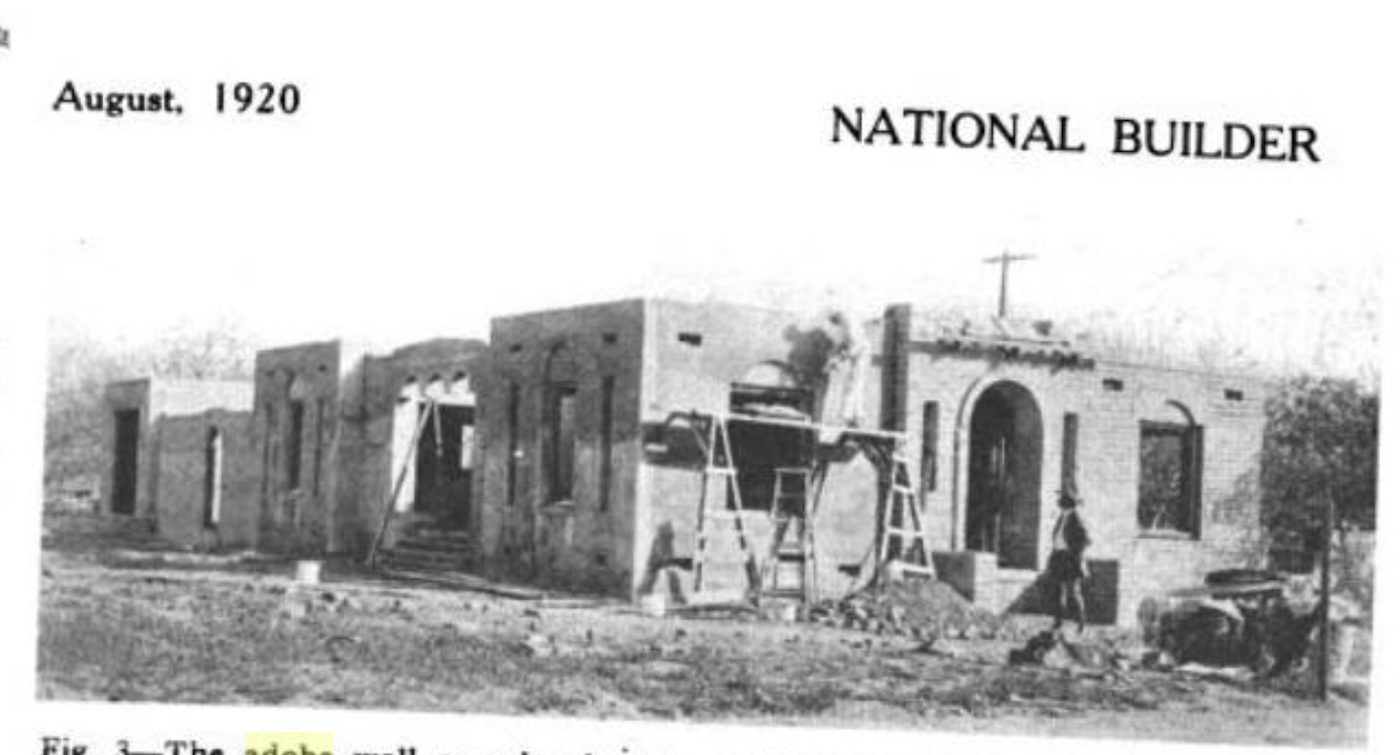

In 1917, to prove the worth of adobe in the construction of houses, he decided to build an adobe house on the family plot at 1129 San Pascual Street as a demonstration of the advantages of using adobe bricks. He had created new techniques and equipment for creating and laying the bricks, special waterproofing to insure against deterioration, and methods for reinforcement.

Adobe, he opined, was economical and usually found on the building site. It was also fireproof and non-conductive, and it provided insulation against both heat and cold. It was everlasting and soundproof. In addition, adobe buildings expressed something of the native beauty and romance of Southern California. His promotional campaign was convincing, and he was asked to add a chapter on “Adobe Buildings” to a 134-page report on city building ordinances.

In 1918, Harry H. Webb, a famous and wealthy mining engineer, commissioned John Chard to design an adobe home for his family in Montecito on Summit Road, on a lot adjoining the new lands of the Santa Barbara Country Club. Chard created a scale model for the house, complete with electric lights and a miniature garden, which was on display at his office in town and drew a notable amount of attention. Shirley Kunze, his niece, remembers this model which came to reside in the yard at 1129 San Pascual Street. It fascinated her as a child with its tiny architectural details and she and her sister used to play with it as children. Unfortunately, years of weather did their worst, and it became a ruin.

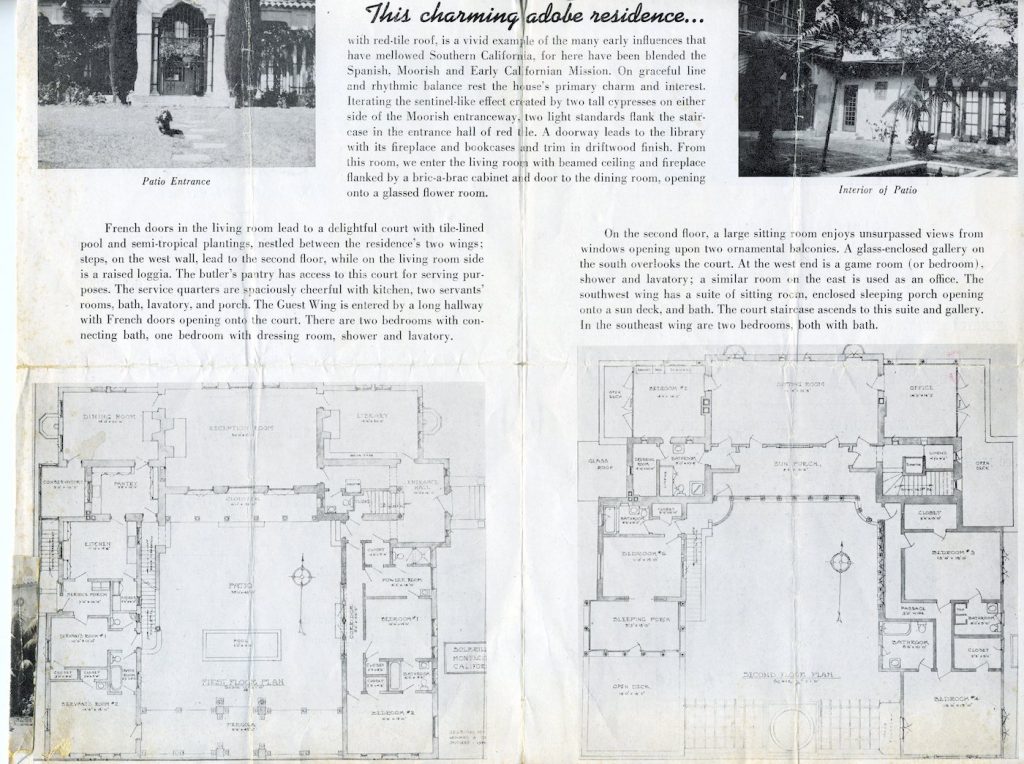

Chard’s landscaping design for the gardens stretched down the hill to today’s Old Coast Highway and became part of the beautiful views from a Moorish court and roof pergola. The two-story house had eight bedrooms and nine bathrooms, a servants’ wing, a library, a conservatory, an electric elevator, and capacious fireplaces. An article in the Morning Press at the time said, “In keeping with Chard’s esthetic, ornamentation on the exterior will be modest in design and the entire effect shows good taste.” Webb dubbed his California home, Solbrillo (bright sunshine).

Another of Chard’s early commissions was an adobe house on the crest of the hill on 10 acres at the end of Anapamu Street. The owner, Hermann F. Sexauer, was invested in several lots in the area and lived nearby. He named the house Sol y Mar. At one point, he rented it to a Romanian couple, Petru and Madame Bochescu, who established a restaurant, art gallery, and playhouse called Vagabondia.

Opening night saw a host of societal luminaries gathered for a savory evening of entertainment. After Madame Bochescu had worked her magic in the kitchen, Petru, wearing a Romanian shirt with red sash and headdress, read his two one-act plays from in front of the great fireplace in the living room. The splashing of water from the courtyard fountain helped set the mood. The

magical enterprise lasted about a month before the Bochescus went vagabonding and disappeared into the anonymity of pre-internet America. In 1920, Sexauer sold the house to Mr. and Mrs. George McConnell who lived there several years.

Chard’s reputation grew, and in 1919 he was hired to design 100 small adobe houses for the subdivision of the Cudahy Walnut Land Company near Los Angeles. Today this area is known as Walnut Park. Coincidentally, three Cudahy sisters lived in Montecito. They would be the main financers of the adobe-style Our Lady of Mount Carmel Church (which is not made of adobe) in the 1930s. The small houses of Walnut Park were touted as being of artistic design combined with utility and livableness.

In 1920, Chard partnered with Handy L. Wass. They designed a home for Mary R. Dennison on the property of the former Boyland school on the Riviera. She was the widow of the president of the Dennison Manufacturing Company of Framingham, Massachusetts. The adobe house was to have 20 rooms and elegant servants’ quarters. Mary was soon involved in Santa Barbara society and travelled extensively.

In 1921, the firm of Wass and Chard built an adobe home for John William Heaney at 2241 Garden Street. In 1922, Chard and Wass dissolved their partnership and Chard designed an adobe home for Ludmilla Pilat Welch and her sister, Anna Pilat Knight. They planned to build it themselves in the Fellowship Colony on the Mesa, and for the most part they did. Chard’s design included a tiled roof, large studio, living room, bedrooms, breakfast room, kitchen, dressing room, bathrooms, and large porch and sunroom.

By 1924, Chard had left Santa Barbara to explore opportunities in Los Angeles and Pasadena, where he is credited with at least two adobe homes, the landmarked Walter Candy House in Oak Knoll, Pasadena, and the Thomas M. Miller House in the Los Feliz neighborhood of Los Angeles. Chard married and lived and worked in the Los Angeles area until about 1950 when he, now a widower, returned to San Francisco to live with his brother Alonzo.

Chard on Adobe

In the early 1920s, John William Chard’s reputation was soaring. A contemporary article in Sunset Magazine touts the use of adobe and Chard. The author writes, “The man who perfected the adobe brick, making possible a new type of construction, is a Spaniard, John William Chard, an architect of Santa Barbara, California. Living in an adobe the greater part of his life, he not only made a study of Spanish architecture in all its aspects but experiments with adobe in the belief that it could be made a practical and economical building material.”

Chard himself wrote an article for California Southland in 1922 entitled “Some Suggestions for Small Houses.” As the fad for Spanish Colonial Revival architecture went viral, Chard had seen only a few examples of good architecture “scattered in a maze of bewildering imitations, importations, and perverted originalities.” When he first heard of the Community Arts Association’s vision for a uniform Spanish Colonial architectural style, therefore, he was cynical, but soon became an ardent devotee of the movement. He was especially pleased with plans for a small house competition that would promote better architecture and make esthetically pleasing designs available to the small house builder.

“A badly designed house loses the opportunity to contribute to the general value and beauty of the community,” he wrote. The elimination of all unnecessary ornamentations, protrusions, and imitations, he believed, was paramount. He became an active volunteer when the Community Arts Plans and Planting Branch created the Architectural Board of Review, which offered architectural advice and plans from qualified designers to the public.

After Chard moved to Los Angeles, he had a regular radio show in which he talked about architecture, specifically adobe. As time passed, however, the popularity of adobe construction dried up, and 1942 found Chard working for Douglas Aircraft corporation in El Segundo. John William Chard died in San Francisco where his brother Alonzo S. Chard was living. He is interred at Goleta Cemetery.

Sources: Works of Hubert Howe Bancroft; Alta California Mission Book, 1770-1855; http://historyandhappenings.squarespace.com; “One Hundred Years of Freemasonry in California Biographies,” http://freepages.rootsweb.com; Interview with Shirley Kunze (niece to John William and Santa Barbara resident); “Old Spanish Trail” by Leroy Hafen, Ann W. Hafen, google books; Contemporary newspaper articles; 1958 real estate brochure for Solbrillo; Assessor’s Parcel Maps; local historian Barbara Goll’s interview with Arthur Chard, Jr. in 2001; City Directories; Ancestry.com resources; glorecords.blm.gov U.S. Bureau of Land Management, General Land Office, homestead search.