Utopia

The quest for the right way to live, the right way to be, and the search for a satisfying and happy life has spanned millennia; just ask Socrates. Between 1663 and 1820 in the United States, besides being a stimulus for emigration from the “old world,” this quest led to the establishment of over 32 American communes, most being religiously based. By 1900, the premises behind communitarian organizations had expanded greatly to include political, metaphysical, and philosophical beliefs.

Despite being hailed by city promoters as a paradise for all, Santa Barbara has seen its share of Utopian experiments ranging from the Spiritualists of Summerland in the late 1880s to the Brotherhood of the Sun in the 1960s and ‘70s. In between, devotees of such movements as aestheticism, transcendentalism, and anthroposophy have made themselves known.

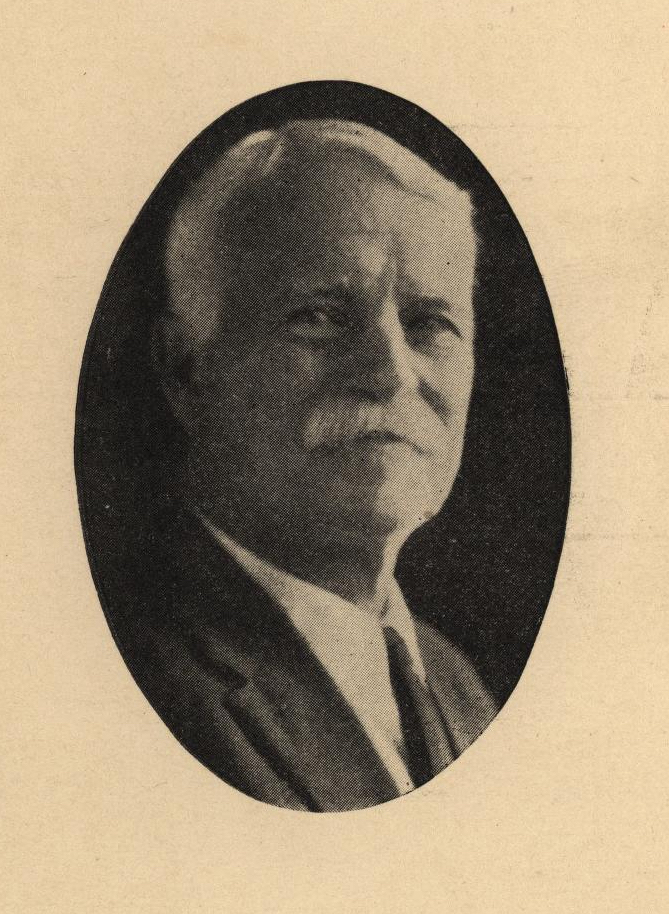

In 1920, a Utopian community was established on the Mesa by a group led by George E. Littlefield and Charles W. Northrup. Littlefield had established at least five such colonies throughout the United States, beginning in 1906 with Fellowship Farms in Westwood, Massachusetts. A former Unitarian minister, Littlefield believed that the way to a good life was to go back to the land and live a simple communal life. At the time, America had become increasingly industrialized, commercial, and citified. In the 1800s, 90% of the American population had been farmers. By 1920, only 30% earned a living by tilling the land, and in 2021, only 1% did.

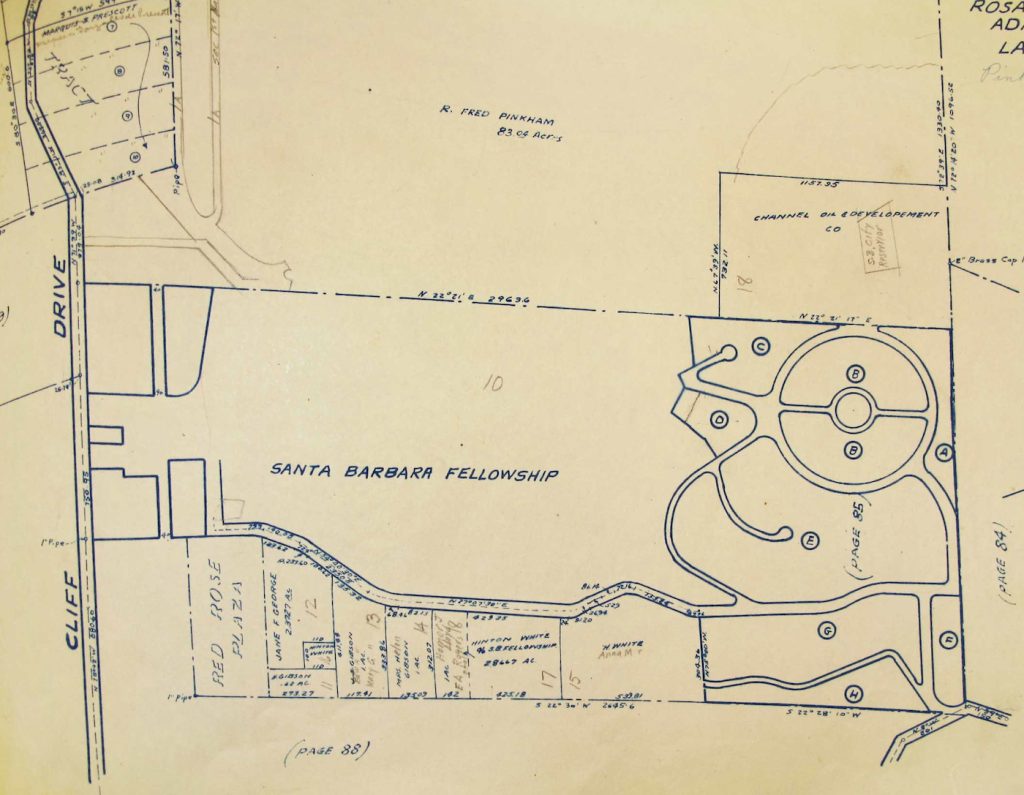

Hoping to create a Fellowship Colony for about 200 families on 87 acres of land they had purchased on the former Rufus S. Pinkham farm north of Cliff Drive on the Mesa, Littlefield and his partners offered the public pamphlets on “the New Thought cooperative colony.” To entice listeners, they hosted a Thanksgiving Day picnic on the property, which afforded stunning views of the Santa Barbara Channel.

Plans for the colony included construction of a main communal building, an auditorium, a library, and a community kitchen and laundry. A cooperative store and an arts and crafts department, as well as a printery (called the Red Rose Press) and an inn, the former Pinkham farmhouse, were being organized.

Charles Frederick Eaton of Montecito, famous local Arts and Crafts artisan and landscape architect, was hired to design the landscaping and assist in platting the lots. Eaton’s plans included a number of small parks and a larger one along the arroyo, where sunken gardens would be developed.

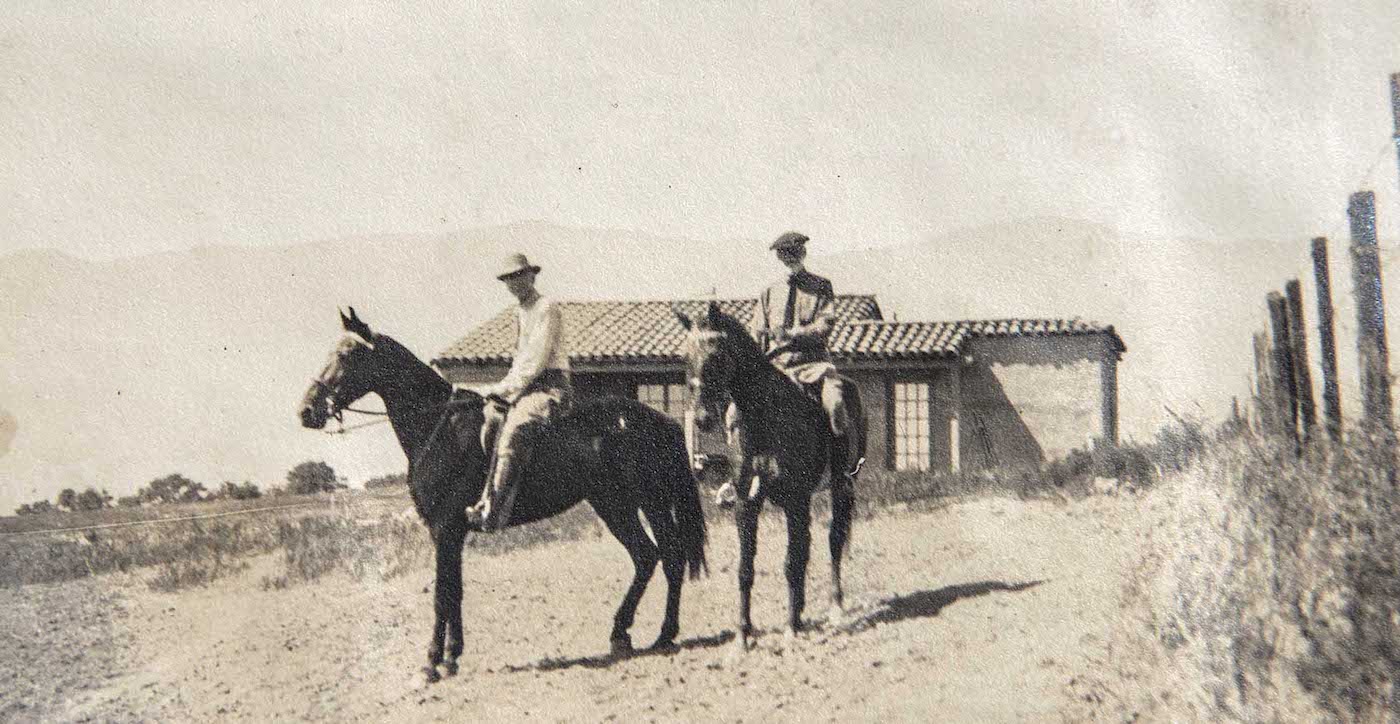

Winding tree-lined roads followed the contours of the land and homes were to be carefully designed to harmonize with the setting, with a preference given to Spanish motifs. A greenhouse and a nursery were also in the planning stages. By May 1921, Fellowship Colony had 40 members. When actor Frank Keenan and his wife arrived that month, excitement mounted as ideas floated about a potential artist’s colony on the farm. Artists were sure to be inspired, they believed, by views extending over scenery that varied “from the delicacy of a Watteau landscape to harsh, rocky cliffs and rolling hills.”

Promoting the Colony

Requests for photos and literature kept the founders busy at their State Street office, and automobiles streamed into town carrying prospective residents. By December, 10% of the lots were already sold. Promotional materials stressed that the way to live life joyously and to the fullest was “to live simply, genuinely, with plenty of outdoors and sunshine.” The founders believed that the way to solve social problems was through education, and the way to develop individuality was in a helpful social environment. Each Fellowshipper would own his own home and have autonomy. They believed that Beauty and Art, creative expression, and the power of thought were the greatest forces in the world. A good life, said Littlefield, has work balanced by play and includes service to others.

Hoping to make Fellowship Colony a center for education, they planned two six-week conferences with speakers and teachers covering a wide array of topics that included science, sociology, metaphysics, history, economics, ethics, music, painting, drama, and film art.

The colony organizers enticed women residents by offering relief from the drudgery of housewifery. “If any woman Fellowshipper is too busy or does not care to cook in her own home,” the organizers promised, “she will be able to secure food from the Community Kitchens or take her family to the hotel, where co-operative buying will make it possible to serve good meals at low prices. Babies can be deposited anytime at the Community Nursery for tender and scientific care.”

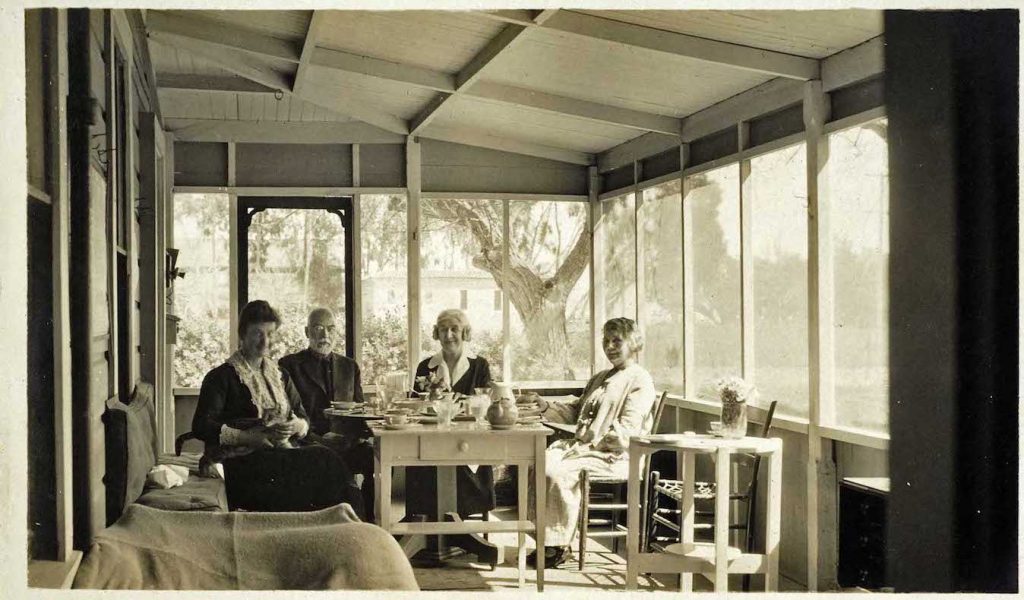

The old farmhouse was remodeled. Additional windows and skylights enlightened the simple structure, screens protected the enlarged porch, and an addition clung to the back of the building. Colorful flowers festooned the yard, and café tables were set up under the spreading palm tree.

A couple from the Atascadero Utopian colony, Septimus and Leila Marten, was hired to run the inn and prepare the meals for the café. “Our little Quaker hostess, Mrs. Marten,” reported Littlefield, “knows all about English muffins and other good things to eat. And hot waffles? – crisp, brown waffles, with real maple syrup! Besides all of which, worth a far more than the price of a meal, is to have just a minute’s talk with Mrs. Marten and to feel the charm of her personality.”

Continued Growth and Impending Strife

In June 1922, artist sisters Anna Pilat Knight and Ludmilla Pilat Welch decided to build a home on one of their lots at the top of the hill in Fellowship Colony. They hired local architect John William Chard (known as the adobe architect) to design a Spanish colonial style house for them, and then proceeded to build it themselves! Although they hired laborers to make the adobe bricks, they helped mix the adobe; and although they hired a carpenter to handle heavy timbers, the rest was constructed by them.

Each day they walked from their home on East Sola to their plot of land in the Fellowship Tract to work on the construction of the house Chard had designed for them. At the time, Chard had just completed the designs for 100 adobe houses on the Cudahy Walnut Corporation land in Los Angeles, as well as an adobe house for Mr. and Mrs. Webb called Solbrillo on Summit Road in Montecito.

For the Pilat sisters, Chard designed an adobe home that included a living room, bedrooms, breakfast room, kitchen, dressing room, bathrooms, large porch, sunroom, and, of course, a large artist’s studio. Completely in tune with the concepts behind the colony, Anna would serve as president of the Fellowship Corporation in 1923.

Promoters continued to attract new members and investors by holding supper meetings at Recreation Center and publishing the Fellowship Weekly, which lauded the attractions and advantages of the community. In October, they celebrated Halloween at the Inn with a pumpkin-hob-goblin party. Another time, the community collected funds to give the firemen a volleyball and net. The trustees of the corporation worked with the city for bus and water service to enhance the attractions of the colony. Speakers arrived to edify the population on a host of topics. On May Day, 1922, the Martins hosted a tea and arranged for music, talks, and visits to the Fellowship pergola on the top of the hill. By this time, however, conflicts of opinion had resulted in the community severing their relationship with George Elmer Littlefield, and he severing his with them.

Nevertheless, lots and land continued to be purchased. In 1922/23 William Hinton White of Boston purchased several lots and took up residence at the Fellowship Inn. He eventually moved into Santa Barbara, however, and opened a real estate business though he remained a trustee of the Santa Barbara Fellowship Corporation.

Despite the best of intentions and lofty ideals about communal living, the inability of the residents of Fellowship Colony to compromise or come to a consensus on a host of issues caused strife in paradise. A harbinger of the final straw had appeared in early 1922 when a portable oil rig was parked for a time on Cliff Drive across from Fellowship Colony. Two years later, pressure to sell or lease to oil producers became unbearable as had the disagreements.

The dissolution of the Colony was announced in nearly every newspaper in the country. In 1924, the Lexington News of Kentucky said, “It is neither a surprise nor a shock to learn that the Santa Barbara Fellowship colony is a failure and bankrupt. The ideals that prompted its organization are commendable, but the idea of getting out to a new place and organizing a social system superior to the one which has evolved through thousands of years stamps such idealist adventures as impractical at the start; consequently, dreams of a new Utopia were once again shattered.”

In 1927, the Channel Oil and Development Company leased 166 lots of the Fellowship Colony. President of the oil company, R.F. Pinkham, whose family had once owned and farmed the land, believed there to be lucrative oil and gas reserves below the lands then being tilled by idealistic Fellowship colonists. That year, Hinton White was appointed liquidator of the unsold properties. White’s belief in the ideals of the colony, however, were not liquidated. The following year, he would publish a collection of his spiritual poems in a book entitled Shrines. (The title poem is completely relevant to the world today.)

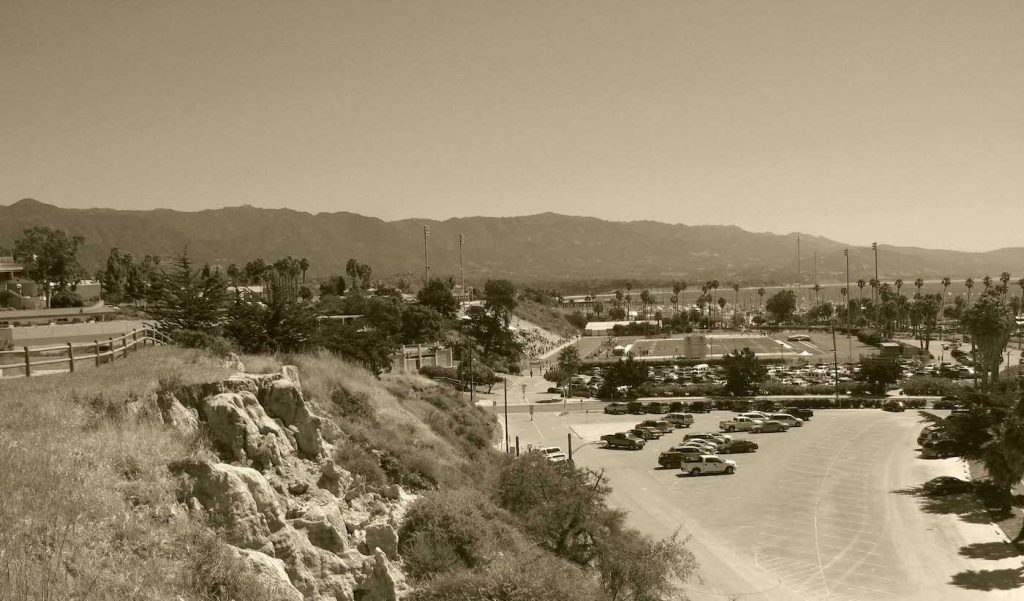

Today, the early street names and a few of the early cottages and adobes built by the original settlers remain: Fellowship Road, Westwood Drive, Red Rose Lane, and White Avenue. The Fellowship Inn, once the 1880s farmhouse for the Pinkham family, still stands, though it is encased by other dwellings and has returned to use as a private residence.

Main Sources: Contemporary news articles, historic maps, “The Fellowship Farm Plan” by George W. Litchfield, multiple internet sources on other Fellowship colonies. Article by Stella Haverland Rouse, Knight and Welch last wills and testaments, Ancestry.com, and historic maps. Many thanks to Bill Dewey, photographer, for giving me permission to use his photographs and those in his possession, as well as sharing the information he had gathered on the topic.