A Successful Prelude: John Dwight Bridge and his Impact on Santa Barbara’s Cultural Renaissance

The moon was nearly full that blustery March night in 1933, when a lone figure paused on the platform of Salina, Kansas, the closest train depot to the geographic center of the nation. Withdrawing the last of his money from a pocket of his corduroy trousers, he carefully placed the quarter and nickel on the platform. From his flannel shirt, he retrieved a half pack of cigarettes and placed it beside the coins. Then, as the wind began to howl through that drought-stricken landscape, he took off his wedding ring and buried it beside the station.

Finding the stationmaster, he asked if there were any work to be had in Salina. He was a painter, he said, and willing to paint houses, doors, fences, or portraits. The stationmaster shook his head — no.

It being late, he was offered a place for the night in the city jail where he slept on a bed of newspapers. In the morning, this renowned artist, whose portraits of high society debutantes and matrons had once commanded four figures, began to walk.

After the first 10 miles, he earned his lunch by drawing a pencil sketch of the children of a gas station owner. Ten miles farther, he earned a bed for the night in a tourist camp by sketching more portraits. His plan was to travel ever westward, doing whatever he could to make his way around the world.

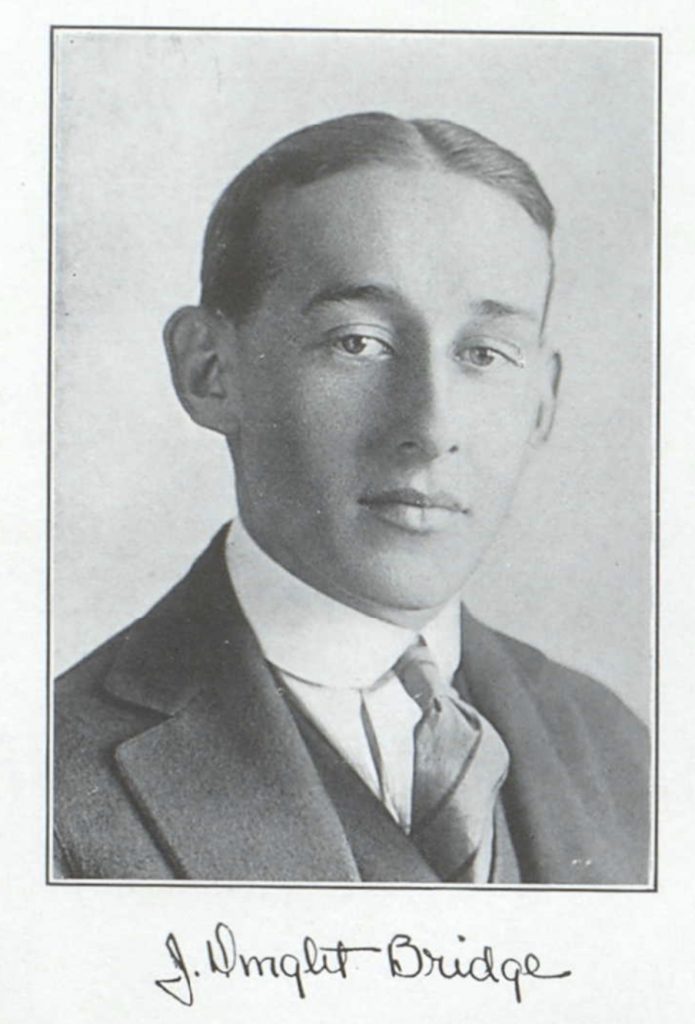

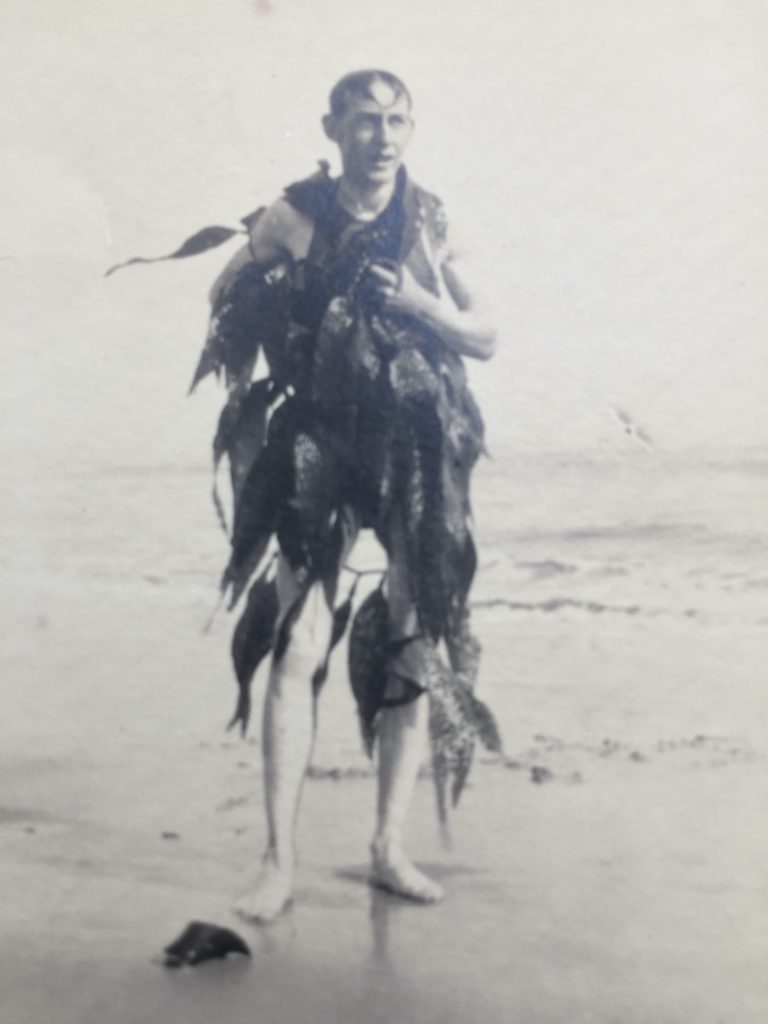

Unlike most people in the nation, John Dwight Bridge had not fallen on hard times, but he was experiencing an existential crisis. The son of a wealthy St. Louis family and a successful artist, he had participated fully in Santa Barbara’s cultural renaissance of the 1920s.

By 1933, however, Bridge had given his entire inheritance to his wife and children, disposed of his elegant wardrobe, and hit the road in search of himself. Thus begins our tale…

Dwight, Everit, and WWI

John Dwight Bridge was born in St. Louis in 1894. He was the grandson of Hudson Erastus Bridge who had left Walpole, New Hampshire, for greater opportunities and settled in the bustling frontier town of St. Louis in 1838. There, he had established a foundry, the Empire Stove Company, and eventually the family fortune.

In 1914, after completing high school at the private boarding school in Pawling, New York, Dwight Bridge enrolled in the Art Students League in New York City. There he became a student and protégé of Albert Herter, famous muralist and portrait painter. He also became acquainted with Herter’s artist son, Everit, who had married Caroline Seymour Keck, the girl next door in East Hampton, Long Island, in 1915.

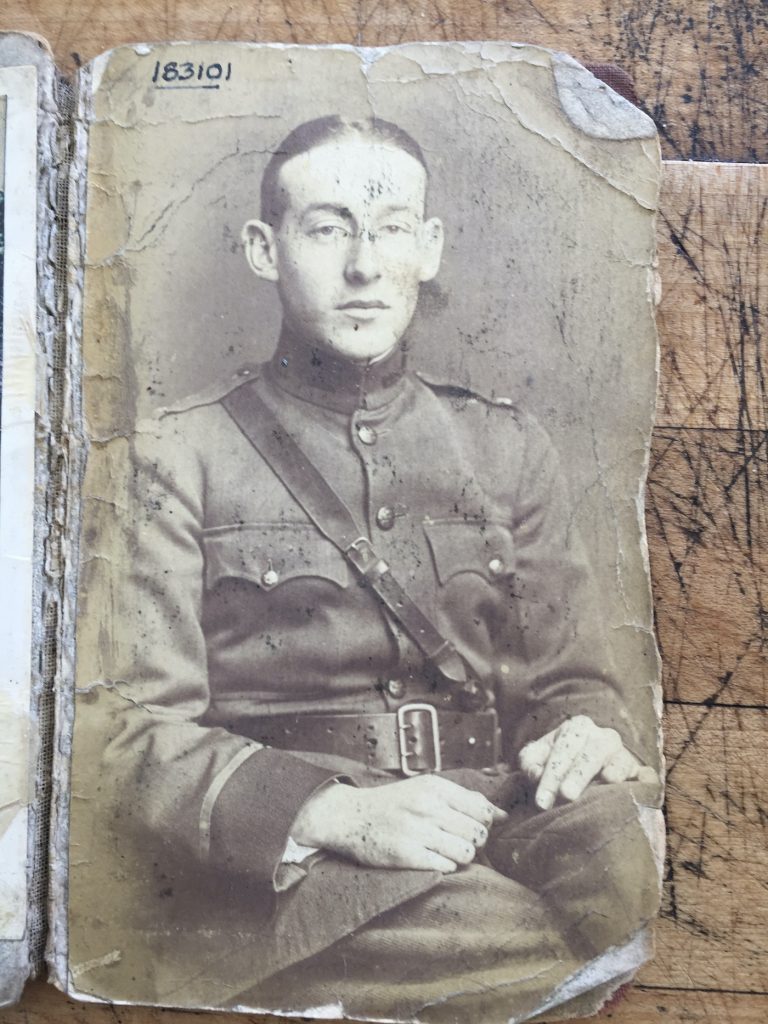

By 1916, Everit, who had spent seven years of his childhood in Europe, was anxious to join the war to help defend his beloved France. On September 4, 1917, he enlisted in the Camouflage Corps. John Dwight Bridge, too, enlisted as a camouflager, and in January 1918, both men boarded a transport ship headed for France.

On June 13, 1918, Everit was wounded while working alone on a gun emplacement in an advanced position at Chateau-Thierry. He managed to crawl to a road where he was picked up by an ambulance and taken to the Catholic orphanage-turned-hospital in the village of La Ferté-sous-Jouarre. He would die and be buried here.

In August 1918, Dwight Bridge received a letter from Caroline asking for details of Everit’s last days. Dwight wrote a letter expressing his great admiration for Everit and telling of the many talks they’d had.

“Life is only real and true if a man loves his wife… True love is life and happiness,” Everit said.

Dwight told Caroline, “So few people understand that the whole war is just a mistake that someone made who did not know what real love was.”

If Dwight and Everit had been mere acquaintances before joining the corps, they were fast friends by the time of his death. Dwight told Ditty (Caroline) how elated Everit was, shortly before his death, to receive word of the birth of his second son and namesake.

“This terrible war brings friends closer and seems to give us the opportunity of opening our hearts to each other,” Dwight wrote, and he promised to secure Everit’s diary and bring it home to Caroline.

Santa Barbara’s Cultural Renaissance

By early 1919 in Santa Barbara, the troops were home and the world pandemic (erroneously dubbed The Spanish Flu), had completed its scourge and departed. A feeling of optimism was in the air and a cultural renaissance was in the making.

A community chorus and two great extravaganzas that involved the entire community in the design and creation of costumes and stage settings as well as acting, singing, art, and instrumental music led to the establishment of the Community Arts Association in 1920. The new organization came to include branches named Drama, Music, the School of the Arts, Plans and Planting, and the Community Christmas Pageant.

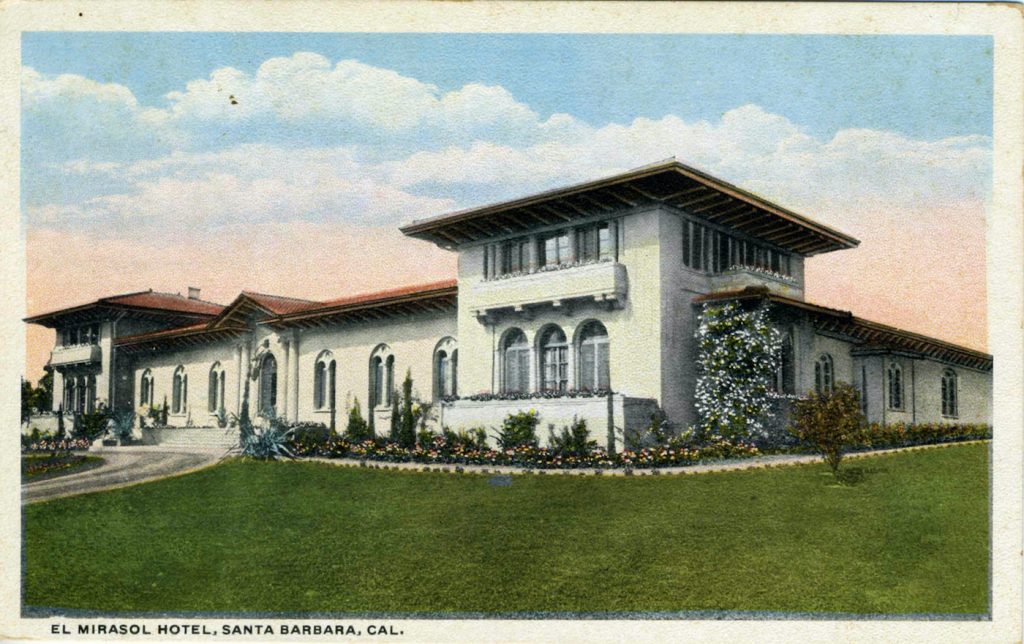

Two of the prime movers behind this renaissance were world-renowned artists Adele and Albert Herter. The Herters had come to Santa Barbara after the death of Albert’s mother, whose estate covered the entire block bordered by Micheltorena, Garden, Santa Barbara, and Arrellaga streets (today’s Alice Keck Park Memorial Gardens). In 1914, the Herters converted her estate into the exclusive El Mirasol Hotel and began to live part of the year in Santa Barbara.

Albert became involved with the Community Arts Players and taught at the School of the Arts, while Adele was responsible for the creation of the Community Orchestra. Both were involved with the first Community Christmas Pageant, creating decorations for the Community Tree of Lights, costumes for the robed carolers, and a series of tableaux inspired by the nativity.

Caroline and Dwight in Santa Barbara

In May 1919, the Herters’ daughter-in-law Caroline Keck Herter and her children, Robert and Everit Jr., rented the MacVeagh house in Mission Canyon for the summer. By July, Dwight Bridge had come to visit. On July 17, however, tragedy struck. Three-year-old Bobby Herter died after eating ant poison. What grief the family must have felt one can only imagine, but two weeks later, Caroline and Dwight were married in a quiet ceremony at the home of a close friend in Pasadena. The remainder of the summer was spent in Walpole with Dwight’s parents at their summer home.

Dwight and Caroline returned to Santa Barbara and purchased a cottage at 15 Pomar Drive in Montecito in January 1920. In May, their first son, John Dwight, Jr., was born. Dwight opened an art studio at the Harmer Adobe on De la Guerra Plaza, and, in July, the Bridges hosted a tea for more than 100 people at the studio. Commissions for portraits started to roll in.

In August, Adele and Albert hosted 150 friends in the romantic courtyard of El Mirasol for a soiree that featured the famous danseuse, Ruth St. Denis. For one suite, Caroline and Dwight participated as patrons of an Arabian coffee house while St. Denis sinuously wove her terpsichorean tales.

At the Pawling School in New York, Dwight had been a member of the drama club. It is not surprising, therefore, that Dwight and Caroline would take to the activities of the new Community Arts Association with aplomb. He joined the staff of the School of the Arts where he taught alongside his mentor, Albert Herter, and became involved with the Community Players.

Dwight the Actor

For the Players, Dwight created advertising posters, worked behind the scenes as a set designer, and acted. For the second series of Community Arts one-act plays, Bridge had a role in The Clod, a melodrama set in Civil War times. For the third series, after his performance in A Night at the Inn, the review said, “Particular mention must be made of the part of Sniggers (Dwight Bridge) which was a characterization worthy of a professional.”

At Christmas time, both Bridges had parts in three of the tableaux organized by Adele as part of her work for the Community Christmas. Dwight was one of the three kings and Caroline played the Madonna for Silent Night.

For 1921, the reviews continued to be glowing. By the end of that year, he had become one of the darlings of Santa Barbara theater.

“Dwight’s past work has proven him to be a comedian of rare ability as well as an actor capable of sustaining the serious straight roles,” said the Morning Press.

Playing the title lead in Booth Tarkington’s Clarence, Dwight earned another rave review.

“Nothing was too good for Clarence, as played by Dwight Bridge. He succeeded in making him so loveable that we liked everything he did, from first act to last,” opined the reviewer.

To benefit the Community Arts Association and promote the concept of community involvement, Albert Herter would present several spectacular productions over the years. The first was Pelléas and Mélisande, which was accompanied by symphonic music composed for it by Claude Debussy and played by the Community String Orchestra.

Bridge was complimented for his performance as King Arkel, the grandfather of the ill-fated Pelléas. The play, written by Maurice Maeterlinck, was essentially a fairytale and tragic love story.

For the Bridges, life was good in the early 1920s. Unfortunately, it was not to last.

Next time, Dwight the Hobo Artist.

[Note to readers: It has been very difficult finding images of Bridge’s work, mainly because they are mostly in private collections. I have been very fortunate to connect with a few of his descendants who have shared images they own. I suspect that there may be portraits painted by Dwight Bridge gracing the walls of many longtime local residences. If you’re willing to share an image and/or could share some information, please contact me at hattie

beresford@gmail.com. Thank you.]

Editor’s note: The following sources were used in this report: Ancestry.com resources; newspaper articles at Santa Barbara Historical Museum and newspapers.com; Community Arts Association drama programs; Herter family papers, Massachusetts Historical Society; Blog by Lynn Bridge; “Camoupedia” by Roy R. Behrens, blog; “Santa Barbara School of the Arts,” Noticias, Vol XL. Nos. 3,4, 1994; “En Souvenir” by Mark Levitch, 2020, Portraits of Remembrance: Painting, Memory, and the First World War; and M.A. DeWolfe’s Memoirs of the Harvard Dead in the War Against Germany; vol. 3, pp. 229-247. Many thanks to Caroline Bridge Armstrong; Mike Stevenson of Guyette & Deeter, Inc.; Alan Fausel, executive director of the American Kennel Club’s Museum of the Dog; and Chris Ervin of the Santa Barbara Historical Museum.

Ms Beresford is a local historian who has written two Noticias for the Santa Barbara Historical Museum as well as authored two books. One, The Way It Was: Santa Barbara Comes of Age, is a collection of articles written for the Montecito Journal. The other, Celebrating CAMA’s Centennial, is the fascinating story of Santa Barbara’s Community Arts Music Association.