The De la Cuesta Family and the Highway

In 1912, Santa Barbara motorists heading toward North County had a major decision to make. Where were they going to cross the Santa Ynez River? There were only two bridges, one near Lompoc and the other, aptly called Mission Bridge, that crossed the river at today’s Solvang. To get to either required negotiating dozens of ravines along the Gaviota Coast and heading over two small steel truss bridges to reach Las Cruces (the intersection of today’s Hwy 101 and Hwy 1) From there, the roads diverged to lead to the bridges.

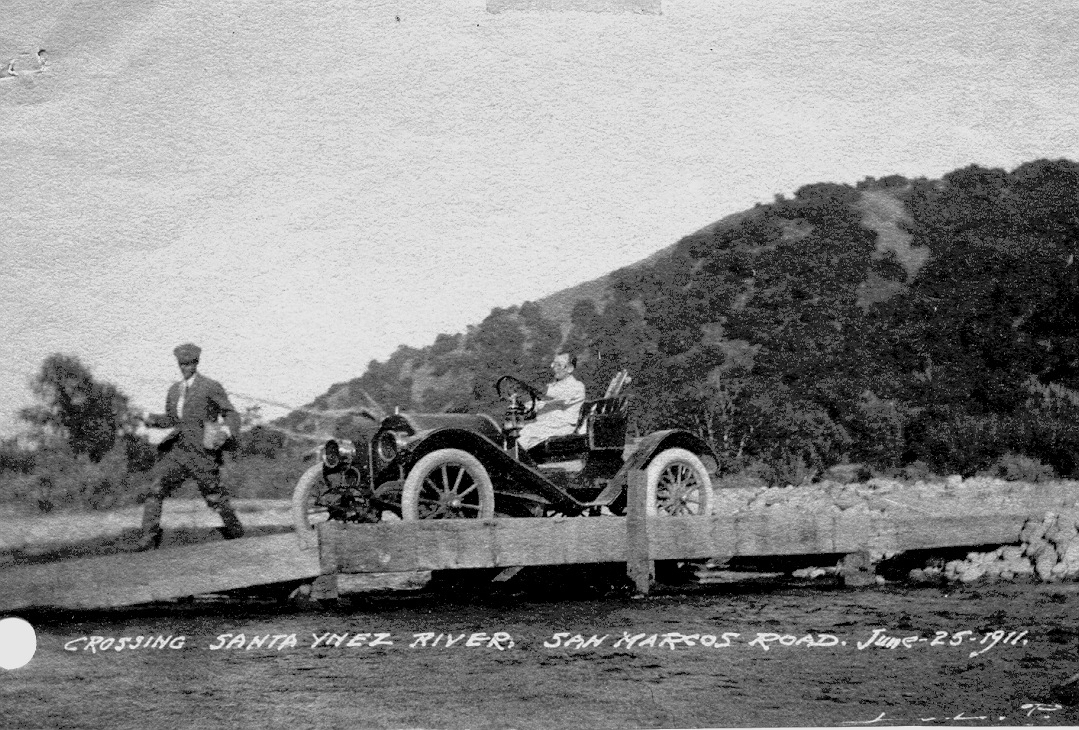

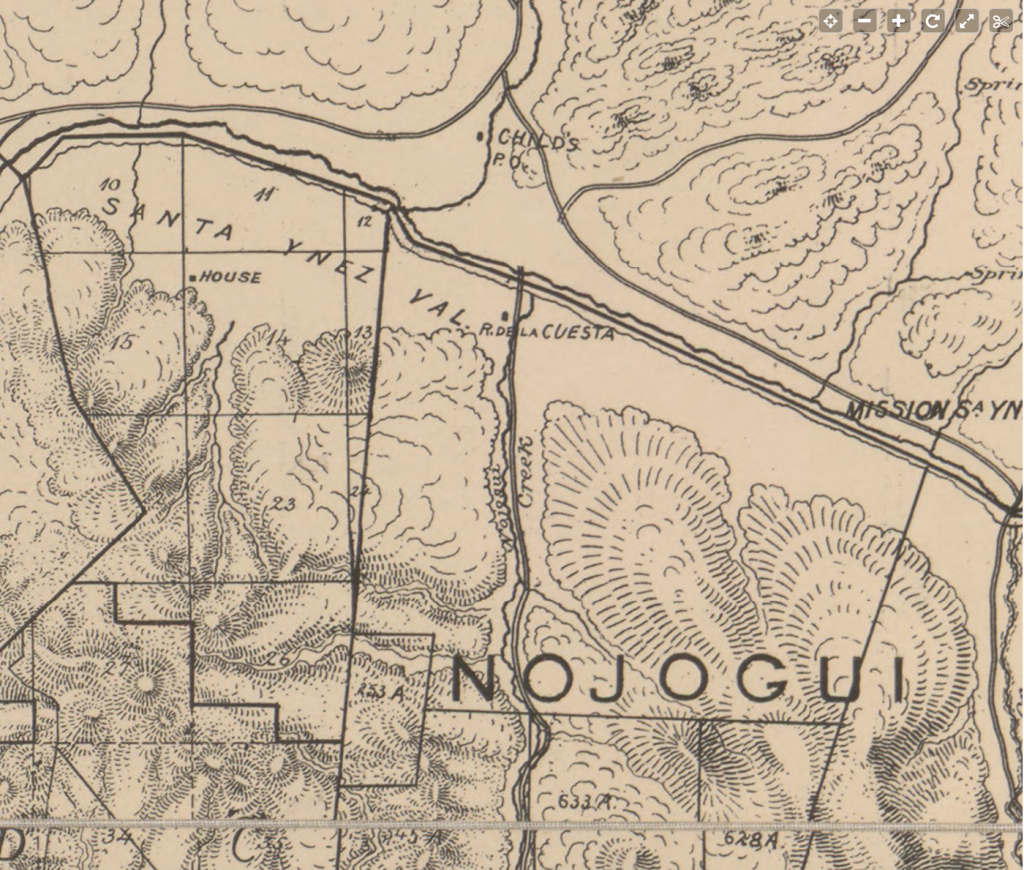

Another option was to continue north along Nojoqui Creek and ford the Santa Ynez River at Cuesta Crossing. This ford took motorists onto the Buell ranch from which several roads headed for parts north. Driving in Santa Barbara County in 1912 was clearly not for the faint of heart. It’s no wonder that many people still preferred the train.

In 1913, the State of California began building a section of the state highway system through Santa Barbara County. It was named Route 2 because it was the second highway system built by the State. Needless to say, heated controversies regarding its route had arisen before it was finally decided to build a bridge at Cuesta Crossing which would lead onto the Buell Ranch where an unofficial town had sprung up to support the ranch’s business.

On the south side of the river, the new highway went through Rancho La Vega owned by the prominent De la Cuesta family who had acquired the ranch in 1851. Cuesta Crossing of the Santa Ynez River was named for them, and members of the family would become influential voices in the development of the Santa Ynez area and the State highway.

The De la Cuestas

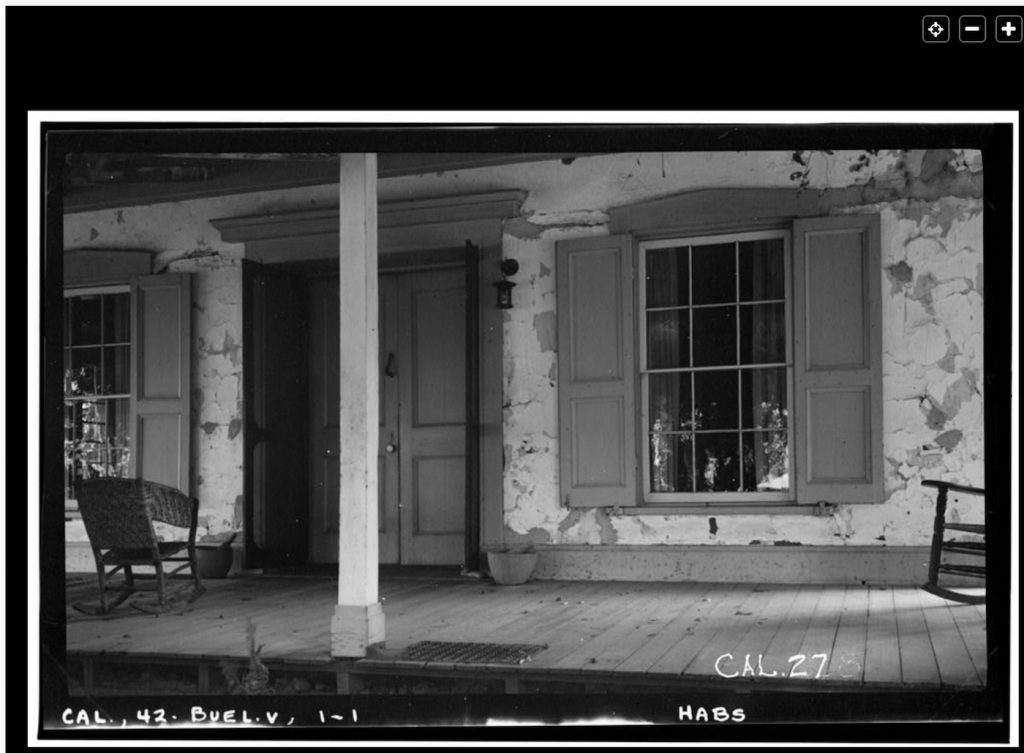

Dr. Ramon de la Cuesta came to California from Spain during the gold rush days and ended up settling in Santa Ynez where he married Micaela Cota and purchased the 8,000-acre Rancho La Vega. In 1853, he built a 13-room adobe for his pending family of 13 people. (He and Micaela would beget 11 children.) He became one of the first doctors in the Santa Ynez Valley, giving his services and medicine for free. At a time when lawlessness was rampant, he and his family were safe from banditos because he gave his services to both saints and sinners.

All the lumber used to construct the house was carried by oxen and mule pack over Gaviota Pass to the site near the Santa Ynez River. The Californios, Indians, and Chinese who built the adobe were then hired as ranch labor and lived on the ranch complex. A census in 1860 listed De la Cuesta’s livestock as 16 horses, 10 milch cows, 25 cattle, and 3,500 sheep. By 1880, Ramon’s employees consisted of three Mexican shepherds, two Chinese hog herders, one Chinese cook, three Californio and Chumash domestic servants, and one Irish tutor.

The De la Cuestas were known for their hospitality, which included offering a bed for the night to travelers since there was no hotel between Santa Barbara and San Luis Obispo in those early days. The artist Alexander Harmer immortalized their spirit of gracious hospitality and their status in the community through his painting La Fiesta de la Cuesta which shows a grand party at the ranch with Micaela Cota de la Cuesta dealing monte underneath the grape arbor. The details in the painting create a vivid portrait of Mexican-era ranchero life.

After Ramon died in 1887, his oldest son, Eduardo de la Cuesta, took over running the ranch. Eduardo had married Elena Pollard, who was a descendent of the Carrillo family and a granddaughter of William Henry Dana whose 1835 visit to Santa Barbara was recorded in Two Years Before the Mast. Besides running the ranch, Eduardo worked as agent of the Santa Ynez Land Company for the sale of the 35,500 acres of College Rancho. Also known as Rancho de los Pinos, the land had been subdivided for homesites by 1889.

Eduardo and the Roads

Eduardo became a political force in the Santa Ynez Valley and served as County Supervisor. In addition to running the ranch, he became a land agent as well. He was quite litigious, however, for the newspapers of the time have endless references to suits in which he was involved. He even sued Bishop Montgomery, the first American born bishop of the Diocese of Los Angeles, for $5,000 he felt was due him as manager of the College Rancho. In another case, he took on the Southern Pacific Railroad for three steers the train had slaughtered, but lost that suit because his men were the ones who had left the gate open.

A strong advocate for improved roads and a new highway, La Cuesta ironically believed himself to be the object of highway robbery on a return trip from the Gaviota pier where he and his wife had retrieved their daughter Ynez who was returning from a tour of Europe in 1913. They had just passed the bridge at Gaviota Gorge when two armed men stepped from the roadside and demanded that they hold up their hands. They complied immediately, but their chauffeur had trouble controlling the car and raising his hands at the same time. With the shotgun staring him in the face, he somehow managed to bring the car to a stop, and he and his passengers quickly exited the automobile, hands over their heads. Expecting to be searched, Eduardo de la Cuesta told the hold-up men his name. “Oh,” said one of the men, “you are De la Cuesta are you? Well, we don’t want you, you can go along.” Turns out the armed men were deputies lying in wait for a stolen automobile supposed to be headed north from Santa Barbara.

With his ranch bordering on the Santa Ynez River and his ability to cross that river depending on access to the ford at Cuesta Crossing, the conditions of the roads were of paramount importance to him. In August 1911, now former supervisor Eduardo de la Cuesta addressed the County Board of Supervisors, and, as the Morning Press reported, “…vigorously denounced the road administration in his locality.” He demanded that a grand jury be called to investigate and verbally attacked Supervisor A.W. Conover by saying, “He’s built a road [down to the crossing] so steep that I take a chance of killing myself and my family every time I try to drive it in a spring wagon.”

As De la Cuesta warmed to his subject, he opened fire on Conover’s entire road force, even the mules. “The road foreman spends more of his time sitting with his back to a tree, smoking a pipe,” he said, “and for days at a time the mules have done no harder work than chew hay and munch grain.” The matter of access to the Cuesta Crossing had been a topic of dispute for some time, and there seemed to be no permanent solution to the problem.

Eduardo’s problems were solved, however, when his lobbying for a more direct route for the State Highway (which meant going through his property) was successful. The State of California decided to build a bridge across the Santa Ynez River at Cuesta Crossing. Work on that bridge began in October 1916 and was to cost an estimated $125,000. The bridge was to be more than 1000 feet long and would include five steel Pratt trusses, approached on each side of the river by earthen berms. Concrete piers were set into the riverbed to carry the trusses.

In September 1919, the Morning Press reported, “The bridge over the Santa Ynez River has been built so strongly that it is believed the floods and high water carrying debris down the Santa Ynez River cannot possibly sweep out the piers.” Though the bridge outlived Eduardo, who died in 1937, it was replaced with a parallel bridge in 1948. At present, Hwy 101 bypasses even this bridge as it speeds its way north on four lanes.

Today, one can still walk the bermed portion of the original bridge where an arbor of pepper trees creates a lovely shaded canopy. Just beyond that, a piece of the span still exists, but the steel trusses are long gone and the rest of the concrete piers stand like lone sentinels leading toward Buellton.

The De la Cuesta adobe and barn, though much altered, still stand today at Mosby Winery at the base of Santa Rosa Creek Road. Once again grapevines grow at Rancho de la Cuesta and Harmer’s vision of Micaela Cota dealing monte under the grape arbor in a time long ago cannot help but come to mind.

(Sources: Contemporary news articles; Los Angeles Times, 7 February 1960; cityofbuellton.com; Ancestry.com resources)