Edwin Deakin’s Missions

In January 1904, the Santa Barbara Independent informed the public that a “very notable art exhibit” had opened at 1212 State St. in the building that recently housed the Chamber of Commerce. For 25 cents, visitors could see the much-lauded oil paintings of the 21 missions of California by Edwin Deakin. “Each of the 21 large pictures that comprise this exhibit is a work of supreme art, and the coloring is simply superb,” opined the Independent.

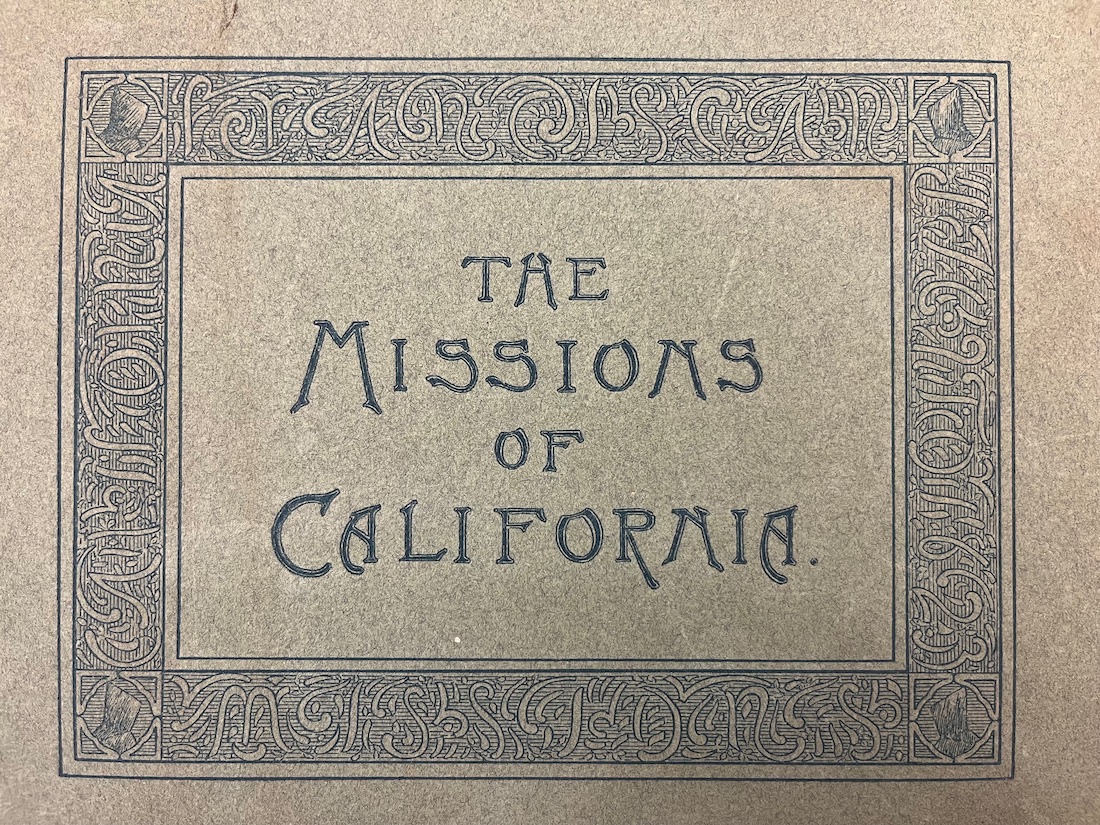

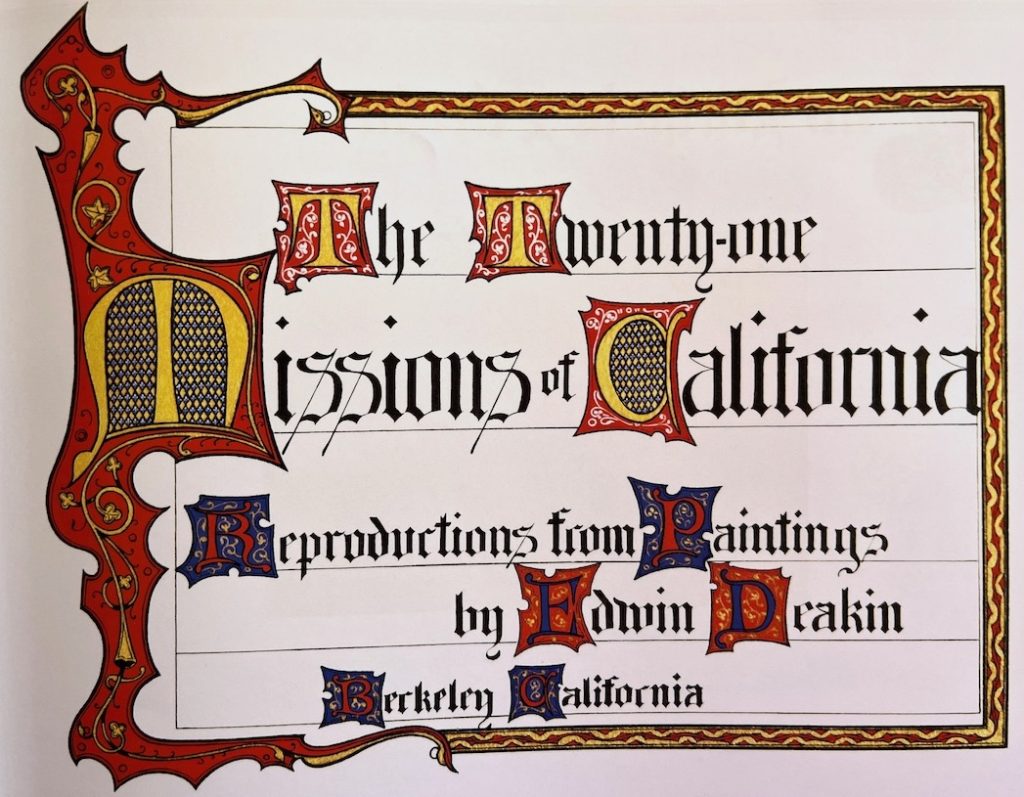

The paintings represented a life’s work and passion and was considered the only notable complete series of the missions extant. Deakin refused to sell them individually and wanted them to be kept together in perpetuity. A book entitled The Missions of California, consisting of black and white photos of the paintings, was for sale for $1.

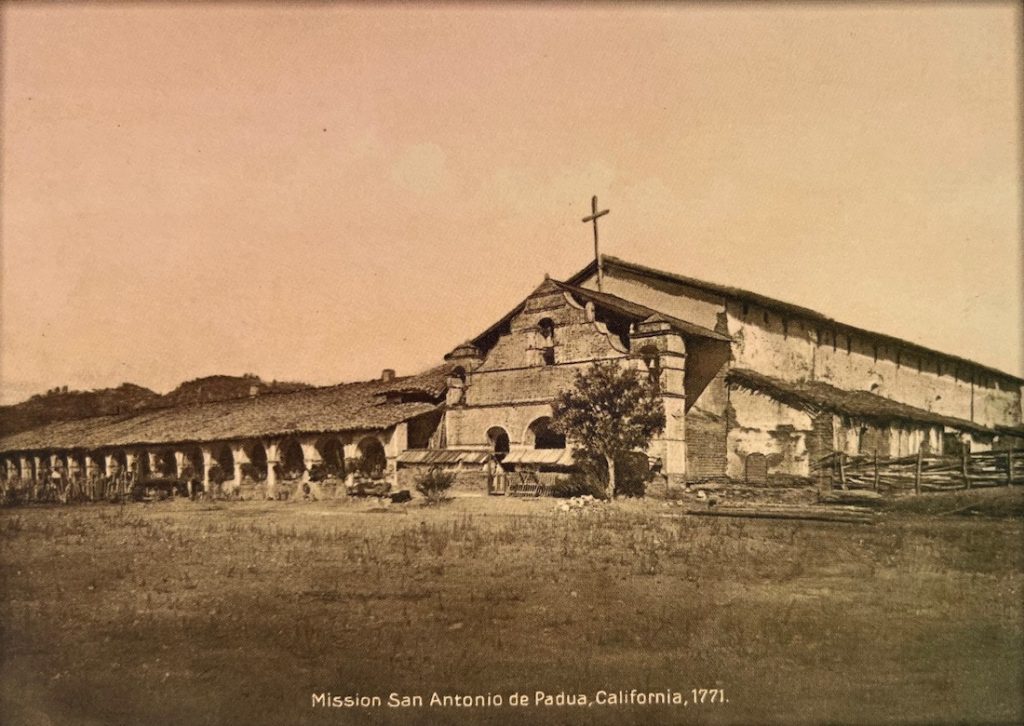

Deakin had carefully studied original photos and accounts of each of the missions to inform his painting, and he was determined to paint the ruins he saw without any modern attachments and alterations. Starting in 1870 with Mission San Francisco de Asis (aka Mission Dolores), he spent 29 years venturing out via wagon, horse, and foot to reach abandoned mission sites to sketch, draw, and paint.

“The paintings, therefore, represent the missions as they left the hands of the original builders,” reported the press, “and before they were ‘improved’ by modern hands and methods by application of cement coating … and other processes that seem to a great many people little better than vandalism.”

Deakin painted two sets of oil paintings and one set of watercolors. He intended that one set of oil paintings go to Rome to be purchased by the Franciscan order, which had established the California missions. From the watercolors, he intended to create a full color book and had created illustrated title pages to contain each image. By the time he died in 1923, however, he had not secured the funds to create his book. His paintings went into storage and were nearly forgotten.

The Missions

By 1769, the days of the conquistadores were long over, and the enlightened despot, King Carlos III, was on the throne of Spain. He ordered the colonization of Alta California and put in place a plan to bring what in his eyes were the blessing of civilization and Christianity to the indigenous population. Franciscan missionaries were to establish missions to teach agricultural and other skills to the native peoples. Beyond the small plots of land given to the pueblos and presidios, all the lands of California were to be held in trust for the Christianized, newly educated and loyal Spanish citizens.

The plan was naïve and impossible and never implemented. Carlos III died and Carlos IV reverted to despotic form, taking away the rights of the criollos (people of Spanish blood born in Nueva España versus the penisulares born in Spain). The criollos objected and fomented a revolution against Spain in 1810. After Mexico won its independence in 1821, the government began to secularize the missions, stripping them of their land holdings and giving large grants of land to prominent Mexican citizens.

Since the missions were not supported by the Mexican government, they fell into disrepair. In Santa Barbara, the Den family purchased the Santa Barbara Mission and kept it from crumbling into a ruin, like so many of the missions in more isolated areas. When Edwin Deakin arrived in San Francisco in 1870, he established himself primarily as a landscape painter, but his first sight of Mission Dolores sent him on a 30-year historic and artistic quest, as well.

A writer in 1901 said that his devotion to an ideal that brought no pecuniary profit was so unusual in money-loving America that he was to be marveled over and admired. Deakin, said the writer, had devoted himself to one great work, “that of preserving on canvas the picturesque architecture and quaint beauty of the old California missions… since a negligent people was not preserving them in reality… [These efforts] became almost a religious conviction with Mr. Deakin.”

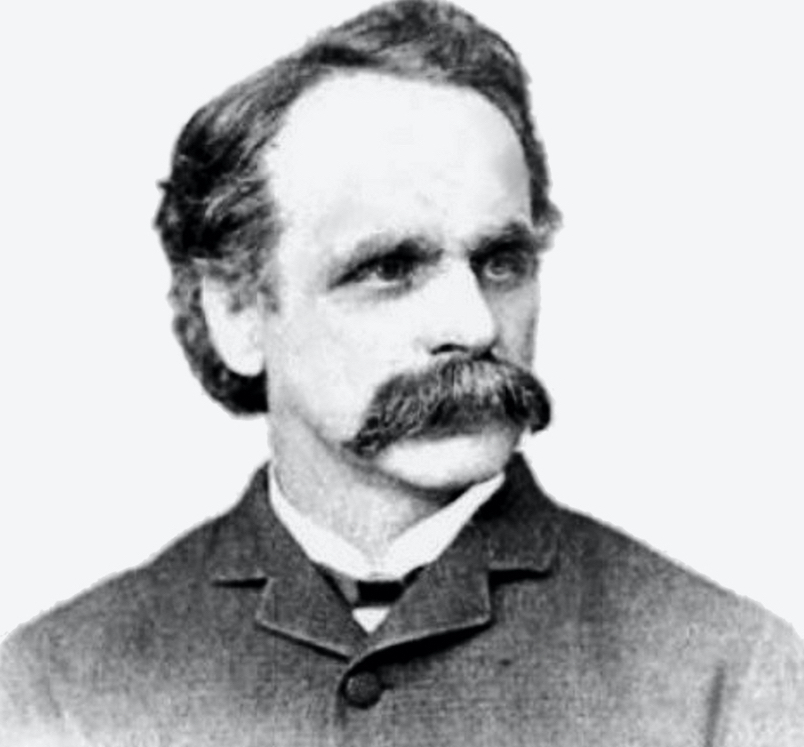

Edwin Deakin

Born in England in 1835, Deakin was 20 years old when he joined his family in immigrating to Chicago, where his father opened a hardware store in 1856. His initial experience with art had come at age 12 with his apprenticeship to a business that painted landscapes and floral designs on furniture. By age 18, he had become a noted landscape artist in England despite having had no known formal training.

In the United States, Deakin married English immigrant Isabel Fox in 1865, and in 1870 they moved to San Francisco, where he joined several artistic organizations and traveled throughout California creating grand landscape paintings of its pristine and dramatic wilderness.

Throughout his career, Deakin spent a great deal of time in Europe, New York, and various cities of the American West as he sought evocative scenes to paint and venues to sell his art. He usually sold his paintings through auction houses, seeming to prefer to have others deal with the business aspect of his artistic endeavors.

In 1899, Deakin exhibited his completed set of 21 missions at his Berkeley Studio. His plan was to later exhibit in other cities in Southern California before sending one set of the oil paintings to Rome to be purchased by the Franciscan order. A reviewer said of these paintings, “They reveal a sympathetic touch, and the poetry that lies in these works of the Old Spanish friars is brought out by the artist’s treatment.” Another noted, “Aside from the historic value, the artistic will make the pictures one of the most noteworthy productions of California artists.”

Writing in 1904, Laura Bride Powers said, “His paintings not only appeal to the eye as a thing of beauty, but they speak to the heart and intellect…. No artist of today possesses so thorough a knowledge of the missions, nor is in as deep sympathy with his subjects.”

Powers found his finest and most appealing painting to be that of Mission San Antonio de Padua. “For a background,” she writes, “a blue bathed mountain lifts its head – the beautiful Santa Lucia. The white-flecked sky and the oak studded valley give to the old ruin the setting that God gave to it, and thus it was that the artist saw in it.”

Preserving the Missions

Over the years, various efforts to preserve the missions started and coughed and sputtered and faded into silence. In Santa Barbara, the “Queen of the Missions” fared better than missions in most places, thanks to the Den family and a dedicated local population who, no matter their religious denominations, loved the old adobe Doña. When she needed a new roof in 1886, the young people of town formed the Go-Ahead Club to celebrate her 100th birthday and raise funds for a new clay tile roof to replace the failing wooden shingles.

By the late 1890s, statewide organizations began calling for restoration efforts for the missions, and they looked to Edwin Deakin’s paintings for inspiration. When the movement to establish El Camino Real arose in the early 1900s, Deakin’s paintings supplied support for the idea, and the Camino itself, it was hoped, would provide impetus to restore the disintegrating missions by making them accessible.

In 1904, Deakin served as an advisor to the California Landmark League which had undertaken to restore Mission San Antonio de Padua. In 1911, a writer said that Deakin’s earnestness “has inspired many clubs to take up the fight for the restoration and preservation of these historic buildings.” In 1919, the San Francisco Examiner and the Los Angeles Examiner, under the direction of a statewide committee led by the American Legion, opened a campaign to raise funds to save the rapidly eroding missions. Images from Deakin’s book of mission paintings were published along with current photos of the increasing degradation.

Today, most of the missions are once again owned and maintained by the Catholic Church, and two are still dedicated to the Franciscan Order. Three missions are owned by the California Department of Parks and Recreation and are open to the public as state historic parks. All are California Historic Landmarks, and Mission Santa Barbara, along with six other missions, is a National Historic Landmark. Deakin’s work continues to be a powerful and beautiful force in preserving California’s storied past.

How two sets of Deakin’s work, one in watercolor and the other in oil, came to reside in Santa Barbara is a story for another day. Nevertheless, bounteous thanks are due the Deakin descendants and the Howard Willoughby and Harry Packard families for making it possible and for honoring Deakin’s desire to keep the sets whole.

Due to a collaboration with the Santa Barbara Mission Archive-Library, the Santa Barbara Historical Museum’s latest exhibit brings these two sets together for the first time in a stunning display of Deakin’s work. The exhibit runs through Fe. 18, 2024. The Museum is located just two blocks off State Street at 136 East De la Guerra St. and is open Wednesday, 12-5 pm, Thursday 12-7 pm, and Friday-Sunday 12-5 pm. Admission is free; donations are welcome.

Sources: Contemporary news articles; Santa Barbara Historical Museum publication “California Missions in Watercolor”; Outlook, 2 January 1904; “The Missions of California” by Edwin Deakin, fourth edition 1901; “The Twenty-One Missions of California,” 1 January 2009, by Santa Barbara Mission Archive Library; Wikipedia and Wiki-Commons.