Native American Chieftain Lithographs

What do these faces reveal? We see Native American Chiefs circa 1838 pictured in two wonderful lithographs. JF owns these two portraits of distinguished Native Americans, and he wants to know how the portraits came to be. Were they painted “on site” in a Tribal village? In a studio? Interestingly, the artist is notable, but the commissioner of the works is the historical personage that makes these lithographs both remarkable and controversial.

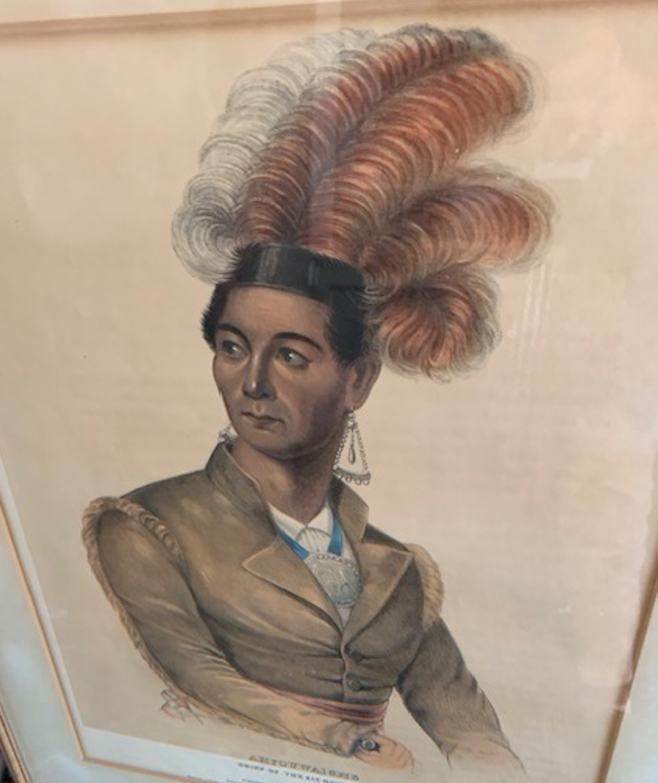

The first portrait is Ahyouwaights, Chief of the Six Nations from 1838, Octavo (a certain size; about 8”x10”), Plate 70, from the portfolio The History of the Indian Tribes of North America, published by McKenney. Second, and also from this portfolio, is the portrait of Chittee Toholo, a Seminole Chief, whose image was published by Greenough, plate 67. The Seminole Chief’s portrait in this lithograph is valued at $2,500 and the Six Nations Chief’s portrait at $700.

A disclaimer: the original works reflect the context and culture of their creation, as oils on canvas for a certain patron, Thomas Loraine McKenney, Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the War Department of the U.S. Government in the years 1824-1830. McKenney was a Maryland Quaker with an important post in Washington, D.C. The oils were painted in that city in the first quarter of the 19th century.

Native American chiefs were called upon to meet U.S. government officials. McKenney requested that Native American Elders and Chiefs “sit” for portraits for the artist Charles Bird King, and his collection was begun in Georgetown in 1821. In 10 years, over 100 portraits were produced by King for McKenney. The artist Bird King was assisted by his talented apprentice George Cook, who painted selected portraits. What is remarkable about the collection is the diversity of the many Tribal Elders in portraiture. The Chiefs portrayed were leaders of large Nations: the Sauk, Fox, Shawnee, Osage, Chippawa, Choctaw, Sioux, Cherokee, Delaware, Seminole, and Blackfeet Nation, to name just a few. Each sitter had their own distinct dress; and because they were visitors to Washington, D.C., perhaps they chose to wear elements of early 19th-century U.S. jackets and military garb.

McKenney’s goal was to form a government collection of portraits of Tribal Leaders that had visited the Capitol. He didn’t offer the collection of portraits to the War Department during their creation: he retained them. McKenney was dismissed from his post at the War Department by Andrew Jackson in 1830; he gathered up his portraits and moved to Philadelphia with the hope that he might find a publisher and a printer, and moreover, a backer for his plan to develop a historical portfolio of images and text.

He found such a person in Edward C. Biddle, a printer, a publisher, and a backer (to be both printer and publisher was rare in those days). Biddle was responsible for the first six hand-colored lithographs reproduced from oils on canvas printed in “Volume One;” the beginning of the portfolio The History of the Indian Tribes of North America, published over a series of years from 1836-1844.

The subsequent volumes were printed up till the 120th portrait, and were offered to the public for subscription sale.

McKenney and Biddle hired the notable judge and writer James Hall, who wrote the accompanying text. His words were guided by McKenney, who hosted the Chiefs as Superintendent of Indian Affairs.

Biddle, the printer and publisher who began the series in 1836, dropped out of the project, which was assumed by the publisher Greenough; who was succeeded by two other publishers, Bowen, then Rice and Clark. The printer-publishers are important to the value of the works; the art market believes the lithographs by Greenough to be the finest.

As well as the importance of the printer, the size of the lithograph is also of importance to value. The Smithsonian owns the folio edition of 120 lithographs in 20 volumes. The “next size down” in book and portfolio printing is the quarto size; my client has the smallest size of two of the lithographs from the series in the octavo size (one eighth of a large page).

Early in the 19th century, although it is unknown when, the Smithsonian acquired a full set of the 20 folios of 120 portraits, as well as the lion’s share of Charles Bird King’s oil portraits. The assession catalogue for the National Museum of the American Indian does not state who donated the works, but 20 years after the last folio was printed in Philadelphia, the Smithsonian Castle in Washington, D.C. caught fire, and the Bird King canvases were lost as were so many other treasures.