Rigs to Reefs: The Sub-Surface Story of Oil Platform Decommissioning

If you live in Montecito or Santa Barbara, you’ve noticed the oil and gas platforms looming on the horizon. Unless you’ve been in the area since the early 1960s, you’ve never known a coastline without their presence. Today, the 27 platforms off the Southern and Central Coast of California are nearing the end of their productive lifetimes. However, the past 60 years have not transpired exactly as they were expected.

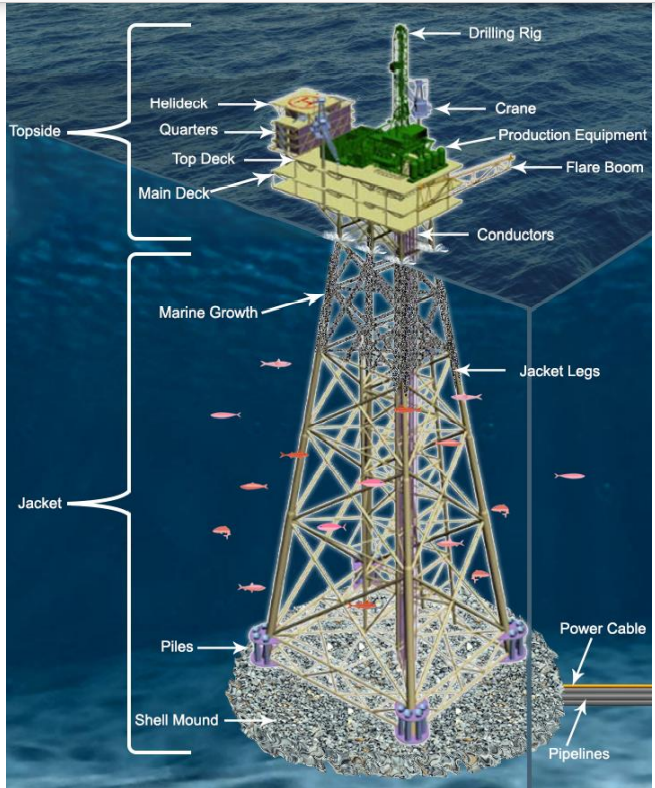

Each rig, massive constructions of steel deployed in relatively shallow depths like 200 feet in the case of platform Holly and depths as deep as 1,198 feet in the case of platform Harmony, are now teeming with life. “You’ve got a platform, and it’s covered in millions and millions of animals: anemones and muscles and scallops and nudibranchs and little crustaceans,” said University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB) Marine Science Institute research biologist Dr. Milton Love. Dr. Love has been conducting marine research for over 40 years with a primary focus in the last 20 on the fish populations making their homes around the oil and gas platforms of the Central Coast. “[Each has] sometimes hundreds of thousands of fish associated.”

According to a paper published in 2014 by marine ecologist Dr. Jeremy Claisse of Cal Poly Pomona, the oil and gas platforms off the coast of California are the most productive marine habitats per unit area in the world. “Even the least productive platform was more productive than Chesapeake Bay or a coral reef in Moorea,” said Dr. Love.

These bastions of industry, symbols of environmental degradation, have become home to more life than anyone could have ever imagined, and based on the regulations, it’s time for them to be pulled from their long-time resting places. According to now retired Outer Continental Shelf (OCS) Oil and Gas Consultant John Smith, 13 of the 27 platforms are now “shut in,” no longer producing oil, and eight of those are resting on leases that have terminated. OCS regulations require full removal of oil platforms and their supporting rigs, which are referred to as jackets, within one year of lease termination. According to Smith, mechanical and abrasive cutting equipment are used to remove most platforms, although explosives may be used in some cases. “So, you disconnect the jacket… you kill all the fish. There’s an awful lot of animals that die,” said Dr. Love. As our world has become dependent on fossil fuels, so too have these millions of animals become dependent on the structures that pump them from beneath the sea floor. “As a biologist, I just give people the facts, but I have my own view as a citizen, which is I think it’s criminal to kill huge numbers of animals,” said Dr. Love.

However, there is an alternative route. OCS regulations allow the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE) to grant exemption from requirement to remove a platform and jacket if it is approved to be transitioned to an artificial reef (or alternative usage). This would mean the removal of the horizon-encroaching platform and top 85 feet of structure below the water line, but the preservation of the remaining steel jacket with all its accompanying marine life. The structure would then become part of the state’s artificial reef program.

Jacket Off

Before we explore the concept of decommissioned oil rigs becoming permanent artificial reefs, let’s explore the prospect of the full removal that, without deviation, is the heading all decommissioning platforms are technically upon.

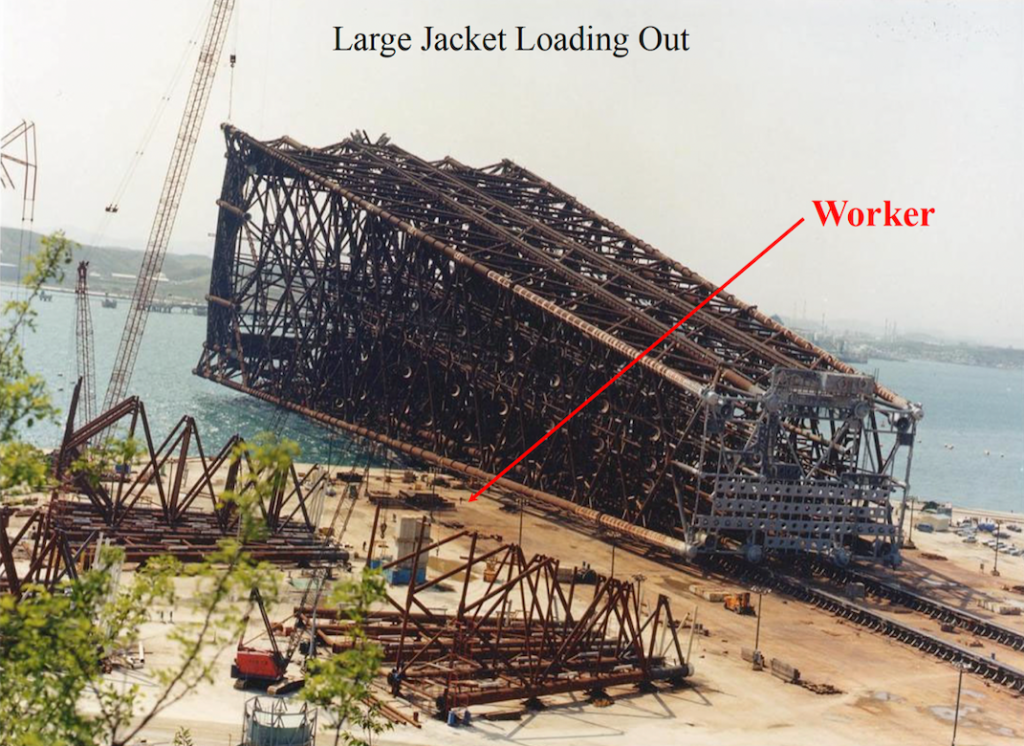

Robert “Bob” Byrd is a structural engineer who has specialized for nearly 30 years on the removal of these structures. Until his retirement in 2015, he was a partner at TSB Offshore, Inc., specializing in providing worldwide oil and gas platform decommissioning consulting and project management services. And although he’s officially retired, he thinks he’ll continue working for TSB as long as he’s physically able. “What most people don’t appreciate is that these platforms are way beyond human scale in terms of size,” said Byrd. Removal of a platform and jacket are conducted by the largest marine vessels in the world like the SSCV Thialf and Saipem 7000, equipped with massive cranes and tons of wire.

“When we’re looking at Harmony and the five Chevron jackets… you’re looking at structures in water depths ranging from 318 to 1,200 feet, the latter depth of which approximates the height of the Empire State Building. So, what you end up having to do is cut those jackets into small pieces…,” said Byrd. “We were going to end up using every large cargo barge available in the world in order to get these things out because you can only put two or three pieces of jacket on one barge.” And per Smith, most of these vessels are currently stationed in the North Sea, Gulf of Mexico, or Asia-Pacific. Dr. Love said that the vessels are too large to pass through the Panama Canal and would need to be brought around Cape Horn, taking many months, and expelling copious amounts of diesel into the atmosphere.

“There just isn’t any real opportunity to take these platforms out in California,” said Byrd. “It’s just simply not possible… I submit you can’t physically do it, today.”

Even so, according to OCS regulations, they must be removed. What if they could be cut into smaller pieces and lugged off by a seemingly endless line of barges? Where would you put all that mass: mass now covered in dead seaweed and marine life?

“If you look at the five Chevron platforms in the Santa Barbara Channel, we figured that you’d need almost 400 acres of coastal property in order to be able to offload those jackets and decks,” said Byrd. He and his colleagues conducted a survey of all the facilities on the West Coast of the United States from San Diego in the south to Puget Sound in the north and found there was nowhere to process them.

“Where it leaves you is the oil companies are gonna stall this thing forever. They won’t do it,” said Byrd. “What we’re trying to do is, is get people to look at reefing in more detail and in particular from an environmental standpoint. It makes no sense at all to take these platforms out completely.”

An Epic Standoff

While new to California, reefing of offshore oil rigs is anything but a novel concept. “All of the Gulf states have active reef programs,” said Byrd. “When an oil company wants to decommission a platform, they’ll go to the Fish and Game [Department] and negotiate a deed of sale. Although, it’s not exactly a sale because the oil companies end up paying Fish and Game. The State Fish and Game people will take ownership of the reef material, and the oil company walks away. They no longer have any ownership and have no liability.”

No liability means that if someone gets hurt diving out by the reefed rig, it becomes the state’s problem. But “the oil companies always [retain] liability for oil and gas [related issues], if there’s a leak, for example,” said Byrd. The oil company is still responsible, though, for plugging and abandoning all wells, which happens regardless of any other factors once they are no longer producing oil. They are also still responsible for removing the platform and uppermost 85 feet of structure before the sale to the state occurs.

Amber Sparks, co-founder of Blue Latitudes, a certified women-owned marine environmental consulting firm helping oil companies and governments turn oil rigs into reefs, works worldwide to facilitate the decommissioning process. After conducting a joint thesis with Dr. Love on the feasibility of establishing a reefing program in California, Sparks and her co-founder Emily Hazelwood started Blue Latitudes in 2015 and their nonprofit, the Blue Latitudes Foundation, in 2018. “In the Gulf, they’ve been reefing for over 30 years and have between 500 and 600 reefed platforms, which are successful ecosystems and are managed by the state,” said Sparks. “[Texas’ and Louisiana’s] artificial reefing programs manage those artificial reefs as they do any of the other artificial reefs within their repertoire.”

However, it’s not so simple in California. The California Marine Resources Legacy Act, AB 2503, was passed in 2010 allowing for the rigs to reef process to occur in state, but contains an indemnification clause, which, upon sale, transfers the future liability of a reefed structure back to the oil company. This transfer of liability back to an oil company does not occur in the Gulf.

“The most important part of this issue is ensuring that decommissioning results in a net benefit to the marine environment, though that is only one piece of the puzzle,” said Kristen Hislop, the Senior Director of the Santa Barbara-based Environmental Defense Center (EDC), a nonprofit dedicated to protecting the local environment. Hislop joined EDC seven years ago after receiving her Master of Environmental Science and Management from UCSB and is an expert on various marine science issues affecting marine policy. “We also have to consider liability that may get passed to the state. So suddenly we have taxpayers responsible for any issues, say there’s a navigational hazard that leads to the loss of a boat or life or anything like that, that gets passed on.”

However, according to Sparks, this type of liability doesn’t appear to be much of an issue. “In all of my conversations [with Texas’ and Louisiana’s artificial reef managers], they’ve never mentioned any sort of major risk or hazard that has been a financial burden in terms of issues of liability,” said Sparks. “That doesn’t mean that they haven’t happened. But in my conversations, that’s never been mentioned.”

John Smith, an Oil and Gas and Renewable Energy Consultant with over 35 years of experience administering platform leases on the OCS and a long-time colleague of Bob Byrd’s, is an expert on the legal side of the decommissioning process. According to Smith, artificial reefs are managed under the National Fisheries Enhancement Act, which has criteria to minimize risks. “The states in the Gulf of Mexico pretty much look at that legislation, and they don’t consider their risk that high,” he said.

“There’s also an issue with cost savings,” said Hislop. Giving a platform to the state avoids the costs to remove the platform jacket and can save an oil company many millions of dollars.

In the Gulf of Mexico, the oil company will donate, usually, half those cost savings to the state during the sale. However, in California, according to Smith, per AB 2503, “it’s 65 to 80% cost share” rather than 50%, and it’s going to be 80% in another year or two. “The industry doesn’t save a lot of money.”

“So, in California, if 23 of our 27 platforms are reefed, there would be approximately $1 billion in saved costs,” said Sparks. “That means $800 million to the state and to an established endowment for marine preservation and conservation.”

Even so, according to Linda Krop, Chief Counsel at the EDC, “no companies have applied for partial decommissioning through [AB 2503].” None of the oil companies are going for reefing under the current legislation as per Smith, “AB 2503 is not considered workable by the industry.”

However, OCS regulations do require full removal of oil platforms and jackets within one year of lease termination. Yet, “the planning and the logistics and the environmental permitting review and so on and so forth takes multiple years,” said Smith. So, it would be effectively impossible for an oil company to go through that process and physically remove a platform within a single year.

The plugging and abandoning process is the only piece that is being completed with relative certainty following lease termination. According to BSEE, all the wells on four OCS platforms have been plugged and abandoned, one is in progress, and another is scheduled to begin next year. The companies responsible for decommissioning these six platforms have been covered in initial decommissioning applications. This means that in theory, the process of removal has begun.

And while the process has begun on paper, Bob Byrd doesn’t buy it: “Today it’s physically not possible to take the platforms out. If people in Montecito want to get rid of these platforms, they’re going to have to give the oil company some legislation to live with.” Locked in an epic standoff, the only path forward seems to be through compromise, a balance to be struck between the transfer of liability, and the cost savings donation percentage. Furthermore, “if a politician down the road wants to renege on any deal like this and tell [the oil companies] to remove something that was approved to be reefed,” said Smith, “then it has to be built into the legislation that the state has to cover some of those costs or has to have some skin in the game.” It sounds reasonable, but it’s never that simple.

State Senator Robert Hertzberg led attempts to modify AB 2503 in 2015 and 2017, both unsuccessfully. “He acknowledged those deficiencies and wanted to address them, but couldn’t work through the issues for some reason,” said Smith.

“That doesn’t mean that it wouldn’t be successful in the future,” said Sparks. California’s oil industry is significantly smaller than its equivalent in the Gulf states. 27 platforms off the coast of California compared to thousands in the Gulf creates a vastly different puzzle. “We don’t have as many citizens that are working on these platforms or going offshore to fish. And as a result, people in California mostly just want to see them completely removed,” said Sparks. “Unless you’re a diver or have researched these platforms, you probably don’t even know that there’s reef ecosystems there. And it’s very easy to misunderstand it and see it as a way for the oil companies to greenwash and save money.”

Perhaps we need a more open, broader perspective. Reefing the oil platforms off the Central Coast would save oil companies money, but it would also create millions in revenue for the state and conserve some of the most productive marine habitats in the world. “Looking at the marine life, the habitats that have been created, [Dr. Love] has shown definitively in my view that there’s a tremendous benefit for leaving these jackets in place,” said Byrd. “It makes no sense at all to cut ‘em up and try to take ‘em out.” No matter your views on oil or the environment, it seems that this issue of oil platform decommissioning and potential reefing deserves more attention and maybe another legislative review.