Stanley Howard Tomchin 1945-2021

Stan grew up spending summers at the Malibu Beach Club on Long Island, where he watched adults play gin rummy. His appetite for learning games was insatiable. As a young boy, he devoured books on poker, gin, bridge, and blackjack. He was allowed to run a poker game in the basement of his home, his parents somewhat in the dark as to how their shrewd son was already developing hustling skills. Stan was booted from the Boy Scouts once word got out that some boys in his troop were losing their allowances to him.

In the fourth grade, Stan subscribed to the Russian chess publication, Shakhmaty, and he studied theory late into the night. He thrived through deepening his problem-solving capacity. From the ages of 10 to 13, Stan would take the train by himself from Long Island to New York City in search of the best players at Marshall Chess Club, Manhattan Chess Club and Chess and Checker Club of New York. He’d absorb it all, watching the play quietly, trying to anticipate moves, or at least understand expert choices. Some would give him a game here and there.

Soon enough, his game seriously developed, and Stan was able to get some coaching from the renowned chess coach, Bruce Pandolfini. At age 12, Stan became one of the youngest ever to win the New York State Chess Championship for his age bracket. In high school, Stan’s chess team went undefeated while winning the Long Island High School Championship all four of his years.

While many find a game for which they have talent and become happily stuck rising the ranks, Stan’s early breadth of interest maintained. Ultimately, he was drawn toward games where you could make money with your superior understanding. He was playing a lot of bridge in his teens, which at least sometimes had some wagering going on. Stan was given a full four-year scholarship to Cornell but found it more stimulating to play bridge all day, so he didn’t hang around long at the prestigious university.

In the U.S., backgammon largely emerged from the bridge community as a fun outlet between intense bridge sets. Stan devoured the limited literature on backgammon available at the time, watched some of the bridge legends play, and soon tried his hand at the game for affordable stakes.

By the mid-1970s, Stan was dominating the backgammon world, winning numerous tournaments worldwide. In 1975, the National Backgammon Association considered Stan No. 1 in the game he loved, and which paid the rent nicely. It was Stan and another backgammon legend, Paul Magriel, who revolutionized the ancient board game by utilizing more math to arrive at best plays than had been attempted or mastered previously.

Later, Stan would find profitability in option trading markets and a significant opportunity in sports betting — as a bettor. Emerging during this time were some gifted computer programmers who also understood sports quite well. Stan’s inquisitiveness and networking skills led him to some of these whiz kids, and he put together a dream team brain trust with great work ethics and solid capital. They took the country by storm, and Stan felt on top of the world.

Unfortunately, what he was doing wasn’t easily understood and assumed by laymen to be just a modern version of bookmaking. Many years into great success, now in the mid-1990s, Stan was charged with 27 felonies, all due to this misconception or convenient misunderstanding as to what he was doing. With 52 character witnesses and a strong case made by Stan’s prominent attorney, a deal was struck and Stan begrudgingly accepted one misdemeanor gambling charge.

Some of Stan’s earliest memories were of listening to stories of the Holocaust and of family members not as fortunate as his parents, both of Russian descent. He credits his mother, Etta, and her generous way for inspiring in him a giving nature, not just with money but with time and energy. At the family synagogue when Stan was studying for his bar mitzvah, he tutored other kids to read Hebrew. In high school, he coached tennis to younger kids — helping make even a little difference — this was an abiding pleasure for Stan.

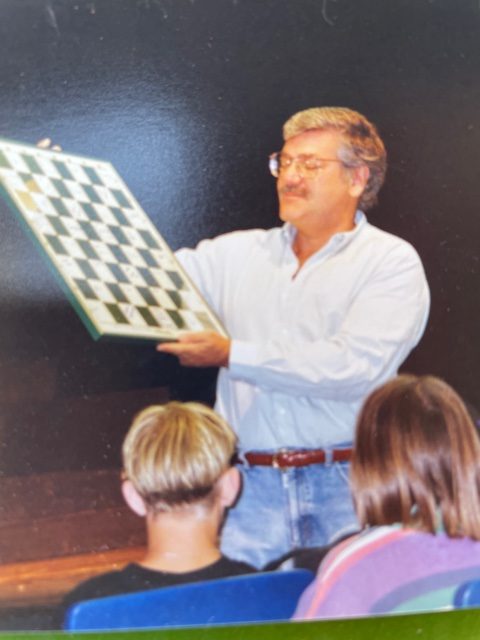

In the 1990s, Stan taught chess to dozens of kids at his daughter’s elementary school on Wednesdays, rarely missing one of those days in four years. He took the top players from Crane County Day School to the state chess championships that last year.

From his teens until deep into his 60s, Stan was a force to be reckoned with on the tennis court. Singles, doubles, coaching — he loved it all. Stan played for years with the Montecito Tennis Mafia, a group of 100 players. In 1998, a team of six was formed to compete in the Phoenix League Championships in Palm Springs, where 3,000 players from all over the world participated. Stan provided coaching and support to prepare, with his team prevailing in a division of 40 others to win the tournament.

Together, Stan and I created a family foundation focusing on health and education of women and children, as well as environmental issues — both nationally and internationally. Stan contributed significant funds to a couple of prominent charities in Nevada, both emphasizing educational support for disadvantaged youth. But he did more than that, as usual, holding special events and shared life lessons. One of his favorite excursions with some of the older aspiring kids, was to take a large group of them to Wimbledon, so they could witness first-hand tennis at its peak.

In the end, I was gifted time enough to say goodbye to the man I loved and with whom I shared more than half a lifetime. His brilliance was a given, but what I’ll most remember him for was his boundless generosity. My mother called him “Stanta Claus.” For me, he was Stanley Bear — to whom I promise to keep good memories alive for his three grandchildren.