The Last Days of Archie McLaren

Her full name is Beverly Aho (though most know her as “Bev Aho”) and, for the past five years, she was the constant companion of the recently deceased Central Coast Wine Classic founder and aficionado of all things grape, Archie McLaren, who passed away February 20th of last year. She and Archie lived in Avila Beach and she was Archie’s lover, friend, soul mate, business partner, and as the end drew near (he was diagnosed with terminal cancer in the fall of 2017), his personal and private caretaker and hospice tender.

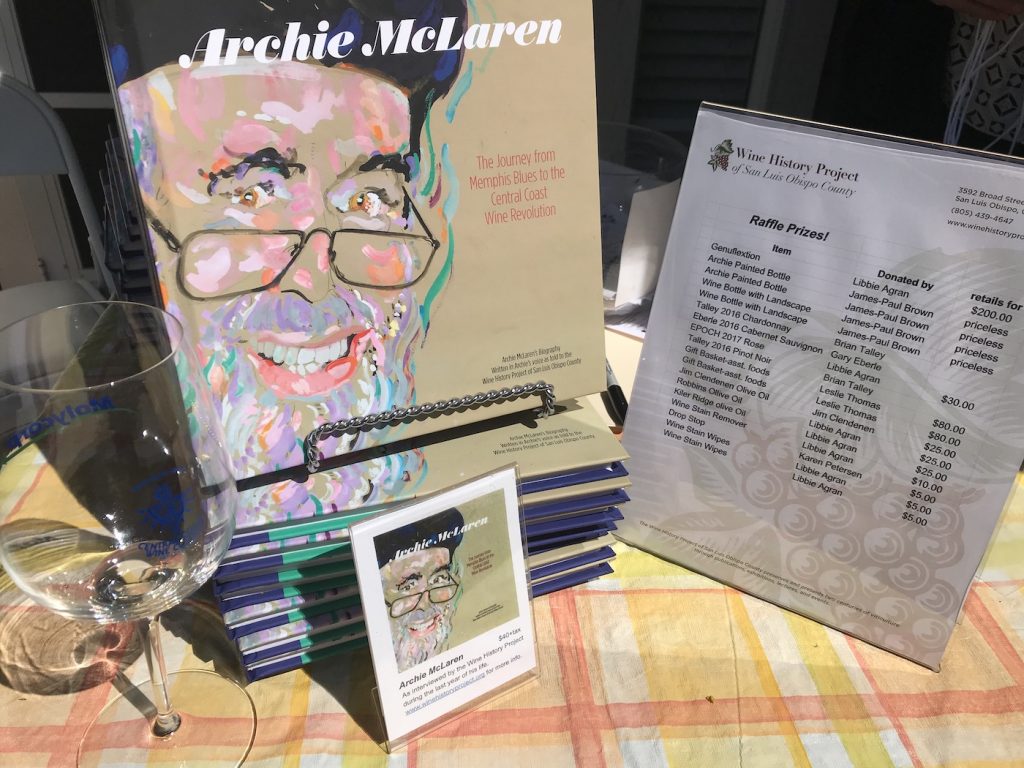

“I helped him through life. I was his executive assistant, and I helped him die,” Bev says matter-of-factly during our conversation after a small event in Archie’s honor at a private home in Santa Barbara. It was also a launch party for the publication of his biography: Archie McLaren, The Journey from Memphis Blues to the Central Coast Wine Revolution, put together by the Wine History Project of San Luis Obispo County. The book traces McLaren’s birth in Georgia and growing up in Memphis, Tennessee and features a touching Afterword written by Ms Aho. The cover of the book sports a painting of McLaren by Archie’s longtime friend, artist James-Paul Brown.

Bev tells me Archie was a poor kid who attended a private school on a scholarship and that the other kids – the rich kids – knew that and held it against him. But, Archie prospered, became Memphis’s public parks tennis champion and led his Memphis University School tennis team. Though just 5’6″ tall, he also became co-captain of the varsity basketball team. He was both an athlete and a scholar and attended Vanderbilt on a full tennis scholarship, which he lost after the first year because of what he described as having become an “over-the-top party boy.” He did, however, earn his BA in 1964, and a juris doctorate at Memphis State by 1968.

The book traces McLaren’s history, his friendship with legendary chef Paul Prudhomme in New Orleans, his first Ferrari (he owned five, though not all at once), his move to California, the launching of the Central Coast Classic, and, well, his storied life.

Archie and Bev met in 2004, when the organization she was with then – Hospice of San Luis Obispo – was a recipient of a grant from the Central Coast Wine Classic, headed up by McLaren.

“He was an elf,” Bev says. “He would walk into a room holding a purse [which she carries now] wearing a beret and the entire room would look and gravitate towards him. He called every man ‘Brother,’ and he had a way of making every man… and woman… his friend. He made everyone feel like they were family.”

But his health began to fade. “He had a stroke in 2006 that he covered very well,” Bev says. “It did not really affect him and within two weeks, he was perfectly normal. When he had his second stroke though, it was pretty devastating. The second stroke,” Bev explains, “knocked his complete sanity off, to the point where he said he didn’t want to live anymore. I wouldn’t let him see himself in a mirror and he asked why. I told him it was because his mouth was crooked and that one eye was drooping.

“So, we shook on a deal: I told him to give me a month. In that month, we’re going to go to physical therapy, speech therapy, occupational therapy, and if none of that works, I’ll drive you to Oregon, pull up residency and we’re going to get Jack Kevorkian in to help you die.”

“You would do that?” he asked.

“Dude, I just quit my job today; this is our job.”

And, for the most part, the new regime did work and he went back to running the Central Coast Wine Classic and other fundraising. However, Archie’s untreated prostate cancer had now metastasized to his bones. He wasn’t feeling good. He was living in Santa Barbara and he thought a gym instructor had caused him to do something that messed up his back. He and Bev went to several specialists and Archie would explain that something happened when this person put him on his chest on a ball. Archie believed the constant pain he was experiencing stemmed from that.

At first doctors couldn’t find anything, but, eventually, they discovered the lesions. “They were everywhere,” Bev says. “They’d been hiding, but now they were on his ribs, his shoulders, the cancer was coming through his bones, bubbling out. There was no way to do anything about it. When we left the clinic, I realized this was now real. His brain didn’t let him hear it; all he heard was that he might have some cancer. I told him ‘No, Archie; it’s everywhere.'”

That was in October 2017; Archie died less than four months later.

“Archie was strong,” Bev continues, “but he wouldn’t let me talk about cancer; he’d cut me off. But, I’m hospice; I’m not afraid of death. I said, let’s figure out how we’re going to work all this. So, I talk with the cancer doctor and ask her to tell me what to do. How do we do end of life?”

“Ethically, I can’t do it,” the doctor says.

Bev told Archie they could move to Oregon. “I told him we were going to go on Toad’s Great Adventure. And we’d get him his treatment.

“She [the doctor] leaves the office, says a few things to Archie, and as we walk out the door, she whispers, ‘Berkeley.’

“So, I said, “That’s my solution?” She says, ‘Yes, Berkeley has an End of Life.'”

Bev found a website, contacted someone, and within twenty minutes got an email asking when they could leave. When they got up to Berkeley, they were asked if they wanted a doctor, “Or do you want to do it yourself?”

Archie at first wanted the doctor to do it and decided he’d die on February 25 (2018), at 3:30 in the afternoon.

But, as the pain required higher doses of morphine and Oxycontin, Archie realized he might not be able to think or decide clearly by the 25th, so called the doctor to see if he could come earlier. The doctor said he couldn’t.

Archie then asked Bev if she thought she could handle it.

She said she could; they told the doctor to “Mail it to us.”

Archie then chose February 20, again at 3:30 in the afternoon.

“The meds were mailed to me,” Bev says. “I opened ’em up. Easy Peasy.

“Queasy.”

They warned her to be patient; that someone may want to die tomorrow and then change their mind.

“Back it up an hour and a half. There are three pills: one is a relaxant, anti-anxiety, two are anti-nausea. One hour before, take those. In an hour, a vial of powder is poured and stirred in a glass filled with apple juice. Archie raises his glass in a toast, salutes everyone in the room and drinks his death.”

In the room were Bev, Archie’s personal attorney, the attorney’s wife, a mutual friend, and a hospice nurse. “Berkeley told us to have hospice there because if we didn’t, the coroner comes in and asks what he took. Hospice takes the edge off,” Bev explains. “This is not pro or against,” she adds. “Hospice is just hospice; they’re just neutral. They stayed with me for seven hours.”

The California End of Life Option Act became effective in June 2016. Archie was the first that anyone knows of to have chosen to take control of his death under those legal auspices and exercise that option in San Luis Obispo County.

Bev says she has the hospice nurse to thank for telling her she needed to leave the room once Archie died. “You don’t want to see him going into the bag and seeing him zipped up,” the nurse said.

“Archie left someone in place,” Bev recalls, “so that I wouldn’t have to be there in the room when they took him away.” And, thanks to the hospice nurse, Bev’s memories of Archie McLaren remain intact as the vital, brilliant, beret-wearing, purse-carrying, wine-loving and generous flirt he was in life.