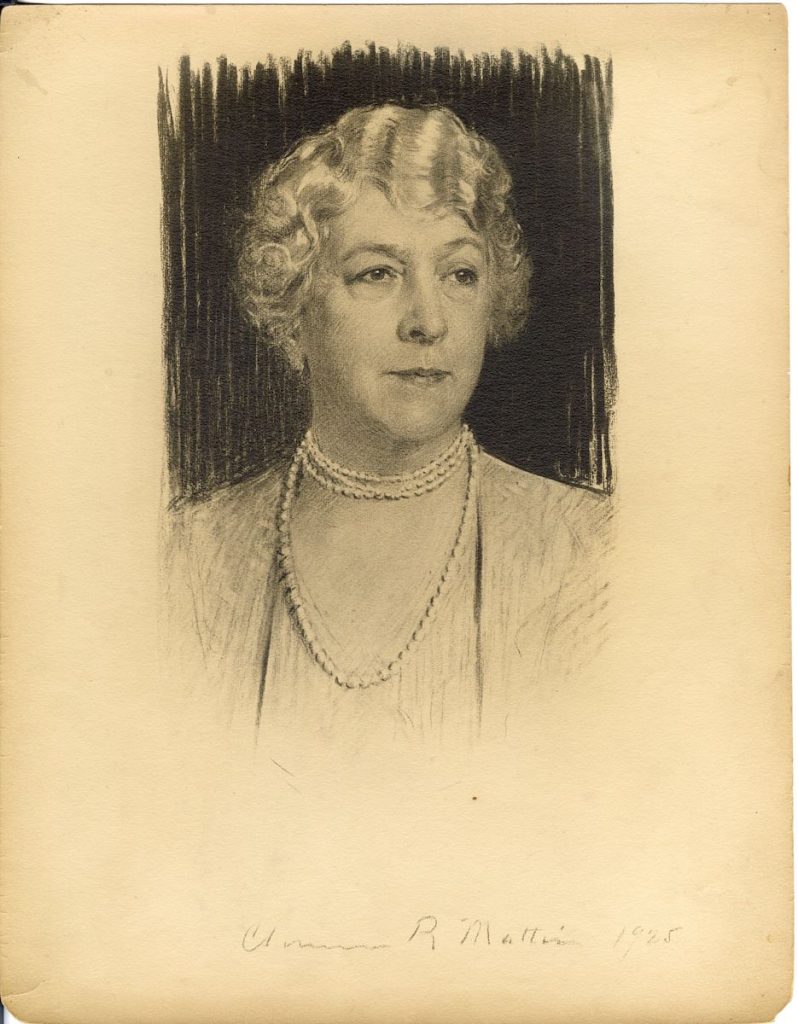

The Artist Clarence Mattei

“Clarence Mattei painted a portrait of our nation from the Pacific Coast to the Atlantic Shoreline… His portraits formed an album of an era which was melding the personalities of the fearless, rugged stagecoach drivers of the Wild West to the quiet confidence and well-bred sophistication of East Coast Philanthropy,” Erin Graffy, local historian, wrote in a 2004 article.

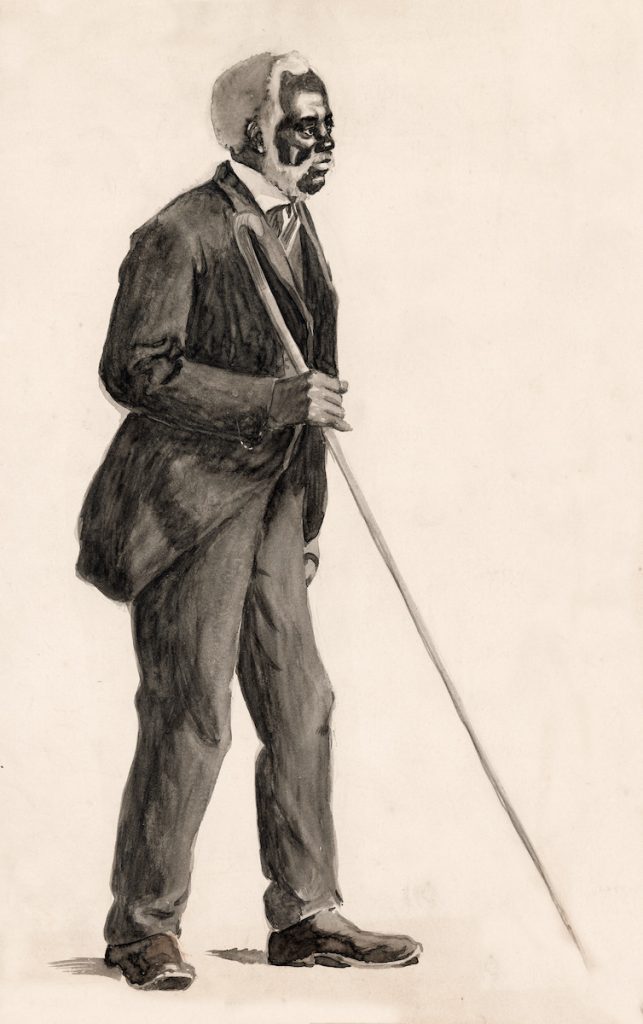

An exhibition of this important artist’s work is currently on display at the Santa Barbara Historical Museum. The portraits range from East Coast visitors, who came to call Santa Barbara home for at least part of the year, to ordinary working men and women from the days of his youth.

Born in 1883 to Felix and Lucy Mattei, Clarence grew up in Los Olivos where his father had the foresight to build a tavern and hotel at the terminus of the narrow-gauge Pacific Coast Railway, which connected to San Luis Obispo and Point Harford. The hostelry’s warmth and hospitality drew visitors well into the 21st century.

One of five brothers, Clarence’s artistic aptitude was evidenced early as he sketched the scenes of the world around him. As a child he taught himself to draw by copying famous paintings. When the New York heir to the Duryea Starch fortune, Harmanus Barkulo Duryea, Jr., brought his bride Ellen Winchester Weld to visit the tavern, Clarence’s life changed forever. Harmanus, who had been wintering in Santa Barbara with his widowed mother and brother since 1888, was an avid horseman and founder of the Arlington Jockey Club and member of the Santa Barbara Club.

At the Mattei hotel in Los Olivos in 1899, Ellen was so impressed with Clarence’s drawings and sketches that the couple decided to place the country boy under their patronage and sent the 16-year-old Mattei to the Mark Hopkins Institute in San Francisco to begin his formal training. From there he would go to New York and become a member of the Art Students League and then to Europe to study and explore a variety of styles and genres at the Académie Julian and elsewhere.

In 1908, Clarence returned to New York and set up a studio where he painted portraits of the elite of the Gilded Age. He also spent part of the year in Santa Barbara and became part of the developing artists’ colony of the 1910s and ‘20s. It seemed an ideal life.

By the early 1920s, however, Mattei had wearied of the more lucrative East Coast art business and told his Santa Barbara friends, “I would rather fish off the edge of the wharf here than paint the finest portrait in New York.” In 1923, he decided to move permanently to Santa Barbara.

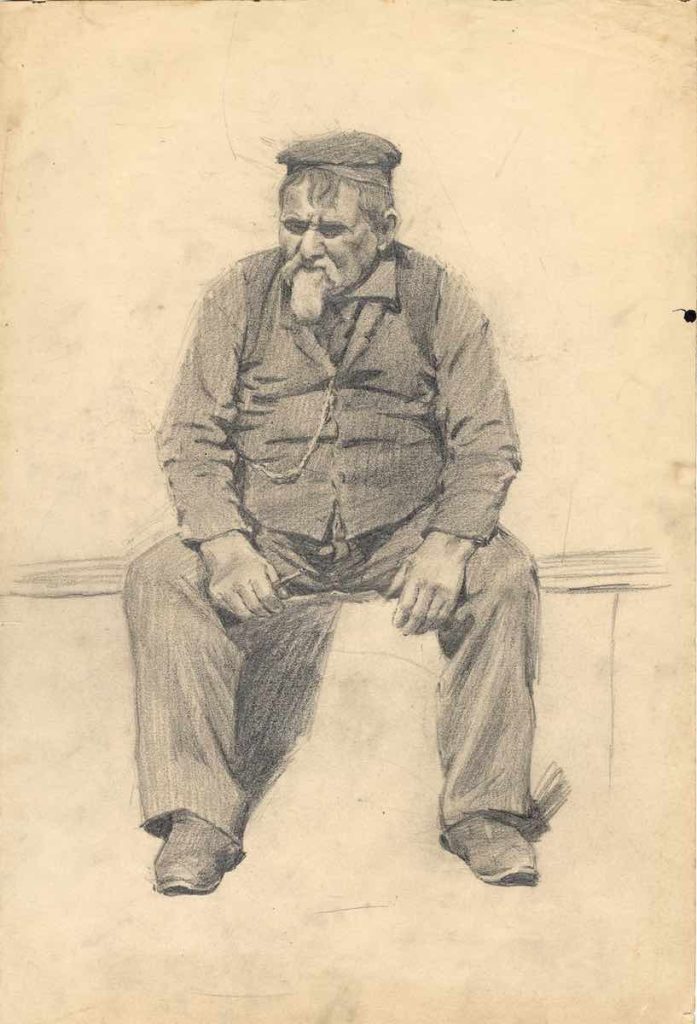

Curated by museum staff in conjunction with Erin Graffy, the exhibit displays a range of Mattei’s subjects and media, as well as photographs of his family and life. In oil, charcoal, pencil, and gouache, his portraiture captures the personality and character of his subjects. While the oils and drawings of business and civic leaders as well as prominent Montecitans are formally poised, a more studious look reveals much about the deeper personages. The pencil sketches of familiar friends and ordinary people are brilliant in expressing through posture and facial expression much about each subject and the historic times in which they lived.

A visit to this lovely exhibition plus the continuing exhibition of the Mountain Drive Community and the permanent exhibit of Santa Barbara’s history is the perfect outing for a rainy afternoon (or a sunny one)! The Santa Barbara Historical Museum is located at 136 East De la Guerra Street and is open Wednesday, 12-5 pm; Thursday 12-7 pm; and Friday-Sunday, 12-5 pm. Admission is free, but donations are welcome. Contact (805) 966-1601 for more information.

(Sources: Noticias, autumn 2004; “Portraits of a Community: The Art of Clarence Mattei” by Erin Graffy; Montecito Journal, “The Arlington Jockey Club” by Hattie Beresford; contemporary newspapers.)