Getting Innovative: From Drive-ins to Zoom Q&As, the Santa Barbara International Film Festival is Ready

Over its 36-year history, the Santa Barbara International Film Festival has had to deal with challenges such as raising funds to keep the fest afloat in the early days; pivoting quickly following the departure of its new executive director after a single season at the helm; and erecting barricades to hold back the masses when stars of the caliber of a Leonardo DiCaprio or Quentin Tarantino arrive at the Arlington.

But never before has SBIFF had to contemplate such an existential question as exactly what it is that makes a film festival a festival.

Is it merely watching a plethora of new movies before they arrive in cinemas or, more likely these days, wind up on a streaming service? Perhaps the opportunity to touch elbows at bars or backstage at the Lobero’s nightly parties to banter about reactions to movies you loved or hated?

Is it hanging out downtown to hear hot tips on the street, or just joining the longest line in front of the Metro 4 figuring that so many other people, like Elvis fans in days of yore, can’t be wrong? Maybe it’s about lingering in the lobby hoping to catch the filmmaker or stars for congratulations or a question? Or does a film festival boil down to focusing on the films?

For SBIFF the answer has always been all of those — and then some.

But, in 2021, it all boils down to one simple query: How do you hold a film festival during a global pandemic?

For much of 2020, SBIFF was hoping not to have to answer that question at all, as staged reopening over the summer seemed to portend that the festival – which had already been moved to early April to accommodate a shift in the date of the Academy Awards – might just make it back into theaters.

But the lingering COVID crisis scotched that thought, and SBIFF watched as various major festivals made their choices: Toronto moved largely to online screenings; Telluride and Palm Springs canceled completely; Sundance went nearly exclusively virtual; SXSW migrated to online; and Berlin did the same for industry-only, while shifting in-person screenings to June.

So, SBIFF was left to build its own hybrid model that balances both safety and access.

It will still incorporate much of what gives the festival its cachet: big-name tributes with Academy Award nominees and other actors from the year’s most important and decorated movies; panels with writers, directors, producers, and other behind-the-scenes filmmakers; and screenings of films from around the world and across a wide swath of genres, including documentaries, foreign language entries and feature films, plus shorts and animation.

There will be a full complement of virtual screenings accessible anytime during SBIFF’s April 1-10 run, in addition to an added attraction in which all of the feature-length movies will have at least one screening at SBIFF’s innovative in-person – actually, in-car – option. To make this happen, the twin parking lots off Cliff Drive at the base off SBCC are being turned into drive-ins able to accommodate 50 cars each for free showing of movies on giant LED screens that are easy to see day or night.

But SBIFF, ever the innovator, wasn’t content to just stick their new screens anywhere.

“We were never thinking about canceling, but we weren’t sure what would be possible,” explained Mickey Duzdevich, SBIFF’s longtime senior programmer.

“Once we decided about having the drive-in, the idea came up that having an ocean view would be wonderful because it’s something different that Santa Barbara hasn’t gotten to experience, and we wanted to make it our own. We also made it free to the community because we just wanted to bring something for people to enjoy, something to do because everybody’s been cooped up inside. This way you can get out and still be in the safety of your own car.”

When Things Kick Off

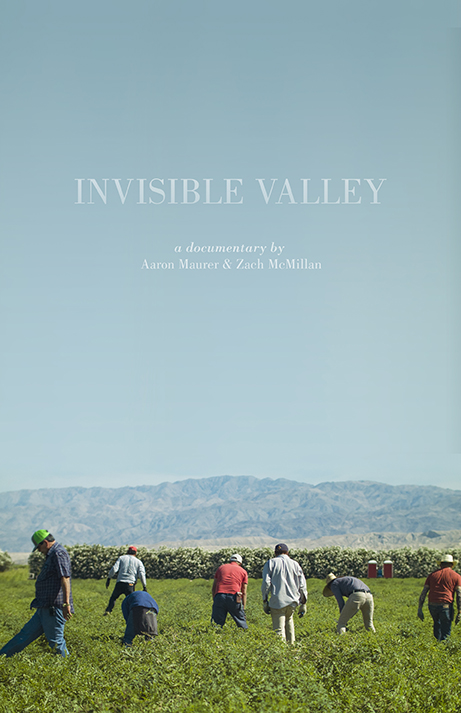

The festival jumpstarts on March 31, with the world premiere of Invisible Valley, a documentary about the latent interconnectivity of various disparate populations in the Coachella Valley. And, as always, SBIFF runs for 11 days and is doing its best to remain as full service as it’s ever been – although nobody will be mingling in person, and parties are not happening at all.

As everyone likely knows by now, the celebrity tributes are still taking place live, albeit sans the glitz and glamour of limousines pulling up to discharge the star in front of the cheering crowds at the Arlington. The feting will also be minus the standing ovations that always accompany the honoree strolling across the stage to take a seat in a cushy armchair across the coffee table from the interviewer.

Instead, the conversations will take place over Zoom. But the list of honorees is as impressive as ever, topped by eight actors and actresses with Academy Award nominations: Riz Ahmed, Maria Bakalova, Sacha Baron Cohen, Andra Day, Vanessa Kirby, Carey Mulligan, Leslie Odom Jr., and Amanda Seyfried.

Plus, the 2021 Modern Master is Bill Murray, not to mention a dozen winners of SBIFF’s Artisan Award, all of whom have scored Oscar nods, and many more to be included among the still-to-be-announced list of producers, directors, and screenwriters.

There will be plenty of Q&A sessions following screenings, albeit video reruns of Zoom conversations conducted with the filmmakers that can be accessed after a viewing.

But there’s no doubt that SBIFF 36 will be unlike any that came before.

“It is going to be difficult, because the whole point of a film festival is to have interaction and talk about films and mingle. That’s what you’re supposed to do,” said Duzdevich, who often works from dawn to past midnight during SBIFF, conducting a good number of the in-person post-screen Q&A sessions himself.

“So, it feels very weird as we are going into this, but it also felt like we needed to do something because it would have been wrong to not have anything. You want to still have that presence and you want to still provide entertainment for your community because that’s what we are in the business of doing. It’s going to be different, but we’re trying our best to keep the conversation going.”

Connecting Online

To that end, SBIFF has built an online forum where people can chat about the films that they’ve seen, ask questions, and interact, Duzdevich said.

“All the staff will be on there as much as we can, too. If I see somebody talking about a movie, I can always jump in and start chatting with them about it,” he explained.

Duzdevich noted that the filmmakers will also have access to the forum, which might make interactions even more likely than in a typical year. It’s paying dividends already, he said.

“I’m actually able to do a lot more Q&A’s this year with bigger names from other countries that normally wouldn’t be able to show up in the theater. That’s been the blessing and that’s probably the best takeaway for the future. Hopefully, when everything does go back to normal, we’ll be able to do these Zoom Q&A’s and actually have them live at the theater.”

See next week’s issue of the Montecito Journal for a rundown on a few of the movies, conversations with filmmakers, and a few of Duzdevich’s picks for movies you shouldn’t miss.

For more details, purchasing of passes and film tickets, and info about reserving a spot at the SBCC drive-in screenings, visit www.sbiff.org.

Invisible Valley: Nuanced Story Out of Coachella Will Debut at SBIFF

Befitting a documentary that encompasses the growing of vegetables and fruits in the expansive Coachella Valley – or Invisible Valley – the film that screens both at the SBCC drive-ins and online on the opening night of SBIFF, had a very organic beginning.

“We made the movie together from the ground up,” said Aaron Maurer, who directed while his lifelong friend Zachary McMillan produced the 87-minute film that explores the unlikely connection between migrant farm workers from Mexico who work the valley’s fields, attendees at the annual Coachella Music Festival, and the “snowbirds” who annually visit Palm Springs and the valley to escape colder winter climes.

“We just worked on it together from the concept that was like a seed to the final edit.”

Invisible Valley got its title from the idea that so many visitors to the area show up just to spend weeks or months enjoying the sunshine in their gated enclaves, or an even shorter span of less than two weeks lapping up what has become one of the largest, most famous, and profitable music festivals in the world. They aren’t even aware of how much agriculture comes from the valley, and even less so of the plight of the immigrants and undocumented laborers who work the land with barely a roof over their heads.

That included the filmmakers themselves.

The only reason Maurer and McMillan – who grew up together in Minneapolis before McMillan relocated to New York – knew of the valley was because each has attended the festival, one time meeting there to partake in partying and headbanging during sets by such metal bands as Motorhead. But it was McMillan’s mother-in-law who turned them on to what was happening on the other side of the barricades.

“She’s one of the snowbirds that goes down there as are a lot of people from Minnesota and the Midwest,” said McMillan during a joint Zoom call with Maurer last weekend. “About a decade ago, she started doing a program called ‘Read with Me,’ a literacy program involving working with children in the school districts outside of Palm Desert.

“She was amazed to discover that there’s a whole other side to the valley, something she had never seen before, agricultural and totally different socioeconomically, mostly migrant farm workers. A long way from the snowbird world of golf clubs, country clubs and swimming pools.”

After volunteering at the schools and becoming more involved in the community, McMillan’s mother-in-law started pitching a piece to raise awareness about the farmworking families and the other population in the valley. When she approached Zach and Aaron, the two decided to do some legwork.

“We were very much aware of our place outside of this world being white and coming from the opposite coast,” Maurer explained. “It was important to us to try to find a different angle. Zach pitched the idea of looking at everybody as a migrant: the workers, the snowbirds who show up in the winter, and the Coachella Music Festival people who come every year for this huge event.

“The whole context of the valley is a really fascinating story and something that we thought of as a microcosm of the wealth disparity and other issues, and even encompassing what’s happening with the environment through the devastation and pollution at the nearby Salton Sea. So many different issues come up when you pull back and take a look from a different perspective.”

The organic approach continued as the filmmakers brought along a skeleton crew and then encountered others along the way who, Maurer said, were instrumental in linking us to other people in the community.

“We were just on the ground, learning as we went along. It was a very guerrilla kind of project. There were so many things that came up and we wanted to cover, but obviously we can’t talk about everything,” said Maurer. “All of the questions and issues that are in the film are the ones that we kept coming back to because you can see how things were interconnected, the themes of poverty cycles, migration cycles, the harvest season. You could trace it like a mad scientist map of how all the issues connected.”

The filmmakers were aware that all of those issues have been covered in everything from news stories to documentaries to TV shows. Which is why Invisible Valley doesn’t come off as an exercise in advocacy.

“We didn’t want to make a classic sort of villain-vs-good guy film that is such a trope these days,” McMillan agreed. “Sure, that’s really compelling, but it also didn’t feel valid for this project because there’s so much more nuance to it. But that creates a whole new subset of problems because if you’re not following that structure, what do you do? What’s the point of making it? Where does the audience member go at the end?”

McMillan answered his own questions by pointing out that the goal became raising questions without criticizing any particular group, even noting in the film that the festivalgoers also save up and sacrifice to make the journey to the festival, which has become as much about community as music.

“We wanted to take a look at personal responsibility, what our actions mean, and how looking at what we do can lead in a very real way to something more seemingly esoteric or vague, like the idea that we’re all interconnected,” McMillan said.

That’s where the Salton Sea came in, McMillan said, noting that it served as a metaphor to combine people from different backgrounds, tying them together through “an exogenous force coming in that creates stakes for everybody and really does imply a connection that isn’t visible.”

What is visible is the cinematography that ranges from action shots at the music festival; hand-held documenting of one poor family’s struggles; snippets of the Read with Me program; the dedication of a new homeless shelter for the migrant workers; sun-lit close-ups and wide angles of the farmworkers climbing palm trees to gather dates; and stunning aerial vistas showing just how short the distance lies between opulent communities and run-down neighborhoods.

Somehow, it all comes together to tell what amounts to a fascinating view of one area just two hours southeast of Santa Barbara.

Which was something of a surprise to the filmmakers, too.

“The whole time, we kept wondering, ‘Is this gonna work?’” Maurer admitted. “For a lot of the time during editing, I kept thinking, ‘I’m not sure we can make a coherent film out of this.’ But it came together once we had the idea of seeing like a diary of our experience down there, a document of what we saw, who we met and opened their homes to us to share their stories, and the themes and ideas that came up for Zach and me. The seasons seemed like a way to anchor it.”

McMillan and Maurer aren’t sure where the film is headed after its world premiere at SBIFF on March 31, when it will enjoy evening showings at both beachside screens at SBCC, as well as online. The festival circuit is likely, but that may depend on how the audience reacts, whether online or by honking their horns as the credits roll down by the drive-in at the beach.

The filmmakers are flying in for opening night, so they’ll be able to hear.