Potter Tales: Genesis

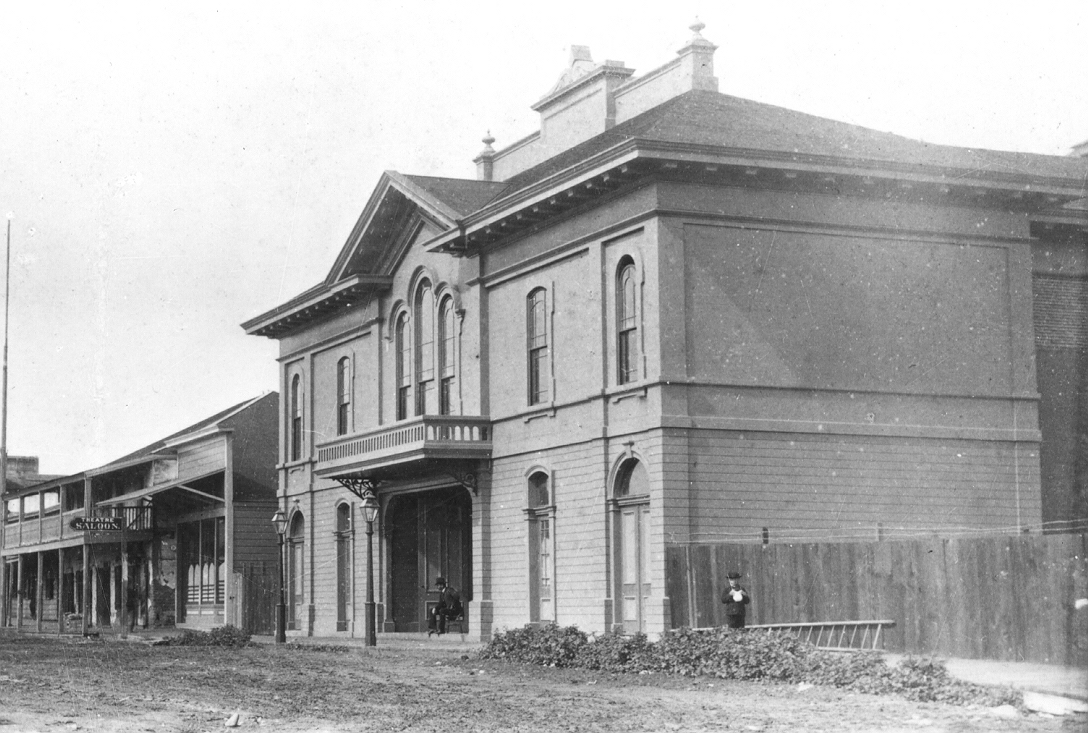

When Jose Lobero expanded the old adobe Sebastopol schoolhouse and created his Opera House between 1871 and 1873, Chinatown was already established on the first block of East Canon Perdido street. At that time, the street was nothing more than a narrow dirt track and an article from November 1873 stated, “This narrow and disagreeable street, … now a Chinese quarter, between State and Anacapa streets, is soon to be widened; thus making the way to the theater agreeable instead of offensive.”

“Soon” apparently meant several years and many complaints to City Council before the street work was actually completed. While improving access to Lobero’s theatre, the new 60-foot-wide street also aided several Chinese business establishments. In 1877, six such businesses advertised in the Morning Press, as did Lobero’s Theatre Saloon and G. Latourrette’s wine and liquor business and bar. On Canon Perdido’s southeast corner with State Street stood John Hubel’s Brewery Saloon.

Despite the improved street, the theater’s location in Chinatown remained distasteful to many Santa Barbarans, partially due to the presence of gambling and opium dens. Many people believed that Chinatown should not be so close to the respectable State Street business area. Pressure to move the district dated from as far back as 1887, when one writer reported that the “pest spot” of Chinatown in the otherwise beautiful city of San Jose had been torn down and removed. He felt this act was worthy of emulation by other cities, implying Santa Barbara should be one of them.

Quest for a New Opera House

The Lobero Theatre was barely 29 years old when a campaign to build a new opera house saw the light of day. Over the years, the Lobero had seen many lessees and several waves of renovations and improvements, but safety, comfort, and acoustic issues continued to plague the venue as much as its location. An article in February 1902 spoke of an unnamed group who had been busy for several months planning to erect a new opera house on State Street and of an unnamed Eastern architect who was drawing the plans. The writer believed it would be completed before the new Potter Hotel was open for business. The summer of 1902, however, passed without any further news of a new theater.

In October, a letter to the Morning Press expressed frustration with the lack of progress, saying that a new opera house was as necessary then as it had been a year ago, but no one was working on it because no one was willing to invest in the project. The writer suggested that the music and drama lovers of Santa Barbara should form a stock company and build it themselves. “The need for a new playhouse was apparent Tuesday evening,” he wrote. “Sousa gave a delightful concert, but it would not have been less delightful had the place been better suited to proper rendition of concert music.”

The pressure mounted, and the Chamber of Commerce gave Santa Barbarans a Valentine in 1903 when it announced they would soon open subscriptions for a new theater and already had promises for 25-30 thousand dollars. They estimated the cost for constructing the new theater would be $60,000, and that it would be completed in several more months. Once again, further reports were not forthcoming.

Plans flickered and fluttered for almost three more years, dying down to ashes and then banked again into a small flame. Then on January 25, 1906, the newspaper headline exclaimed “MODERN OPERA HOUSE FOR SANTA BARBARA WILL BE ERECTED SOON – Property Has Been Purchased and Work Will be in Progress in the Very Near Future – Milo M. Potter is Interested.”

Breaking Ground

The new theater would stand on the southwest corner of State and Montecito Streets. John Lagomarsino, pioneer Ventura resident, farmer, banker, and owner of the Lagomarsino Theatre in Ventura, spearheaded the project along with four other investors. Lagomarsino had business interests in liquor and wine distribution in Santa Barbara. S.L. Shaw of Ventura, who had designed and built Lagomarsino’s theater, was given the contract for the new opera house. He based his design on the 1904 Belasco Theatre in Los Angeles.

Now that things were really moving, Contractor Augustin L. Pendola broke ground on February 23. Peter Poole was hired to do the stone foundation work from which would arise a three-story brick building fronting on State Street. Much of the work would be executed by, and the materials supplied by, local businesses. The 10,000 bricks needed per day, for instance, were manufactured at the Coleman brickyard on Milpas Street.

Each of the upstairs floors contained eight large rooms with baths for lodging which were leased to a hotelier to manage. On one side of the entry, a grocer set up business, and on the other, a saloonkeeper established a bar. H.A. Rogers, manager of the Santa Barbara Opera House (Lobero), leased the new theater for three years and endeavored to manage them both.

As the new theater approached completion, the plan for the proposed drop curtain ignited an inferno of protest. The curtain was to have advertising on it! Many Santa Barbara theater lovers believed that a model, up-to-date theater should not be cheapened by advertisements. Members of the Women’s Club took up the matter, and Mrs. Christian (Mary Miles) Herter, whose home later became the exclusive El Mirasol Hotel, gathered signatures for a petition pledging non-support of any business that advertised on it.

The names on the petition read like a list of Who’s Who in Santa Barbara society of the day. A few names, which may still be recognizable today, were Gould, Hazard, Fernald, Stow, Spaulding, Eaton (Arts and Crafts artisan) and, with Francheschi, Southern California Acclimatizing Association, Doulton (Miramar), Hollister, and Oliver (Rocky Nook Park). The Morning Press published 78 names and said there were “many others.” It was to no avail, however, for after much discussion the Potter directors decided to go ahead with their original plan.

Construction delays, and perhaps the protests, had pushed the official opening to January 29, 1907, but when that first audience filed in they found a thoroughly modern theater where comfort and safety and convenience were paramount. Between the main floor with six loges and four stage boxes and the upstairs balcony and gallery, the theater seated 1,175 people. Many of the seats were upholstered and there was a comfortable waiting room for the ladies. Many emergency exits and a fire resistant asbestos curtain, donated by Milo Potter in exchange for naming the theater after his hotel, insured safety.

One of the most striking features was the proscenium arch that framed the stage. It included ornamental staff work and real paintings, statues, and studies in bas relief.

Finally, the Potter Opens

For its gala opening, the Potter presented the musical comedy The Umpire, featuring the same cast that had played over 350 wildly successful nights in Chicago, where its catchy music and “the most agile and graceful group of little dancing beauties that ever did a jig-step,” had entranced Windy City audiences for nearly a year. With book and lyrics by Will M. Hough and Frank R. Adams and music by Joseph E. Howard, the rather zany plot centered on an umpire whose egregious baseball call brought down such venomous threats that he was forced to flee to Morocco. By officiating an all girls’ football game there, he finds redemption and love. Throw in eight new songs, including “How’d You Like to be an Umpire,” lots of dancing, and a real football game between the girls, and the play was a smash hit.

Though the paper enthused about the christening of the “finest theater” in the West and the entrepreneurial energy that had made it a reality, they also admitted the audience was not so large as it could have been. They blamed the weather, but only two of the 78 prominent citizens who signed the petition against the advertising curtain attended. They were Louis Stott and his wife, Ethel, who was “strikingly gowned in a crush strawberry creation.”

Never-the-less, the Potter was suitably launched and quickly became the theater of choice, offering a steady stream of entertainments each month. During that first February, its lights were rarely out, as it brought such varied acts as McIntyre and Heath’s vaudeville company, for whom W.C. Fields was a principal member. Community theater was represented by the annual production of St. Anthony’s College, and “legitimate theater” was represented by Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew. That month, the stage was lit for 15 out of 28 days.

Faced with this abundance of competition, the old Santa Barbara Opera House (Lobero) soon fell into decline and after several years was rarely used. Ultimately, it would arise phoenix-like from the ashes in 1924, while the Potter would succumb to the Earthquake of 1925. Though brief, the Potter years were not without import and influence on the future of music and drama in Santa Barbara.

Next time: Glory Days at the Potter

(Sources: contemporary newspaper articles; 1907 and 1913 Theater Guides; ancestry.com sources; losanglelestheatres.blogspot.com by Bill Counter; biographical information from various internet sources; Plie Ball! Baseball Meets Music and Dance on Stage and Screen by Jeffrey M. Katz, pp 40-41; California: A History by Andrew F. Rolle.)