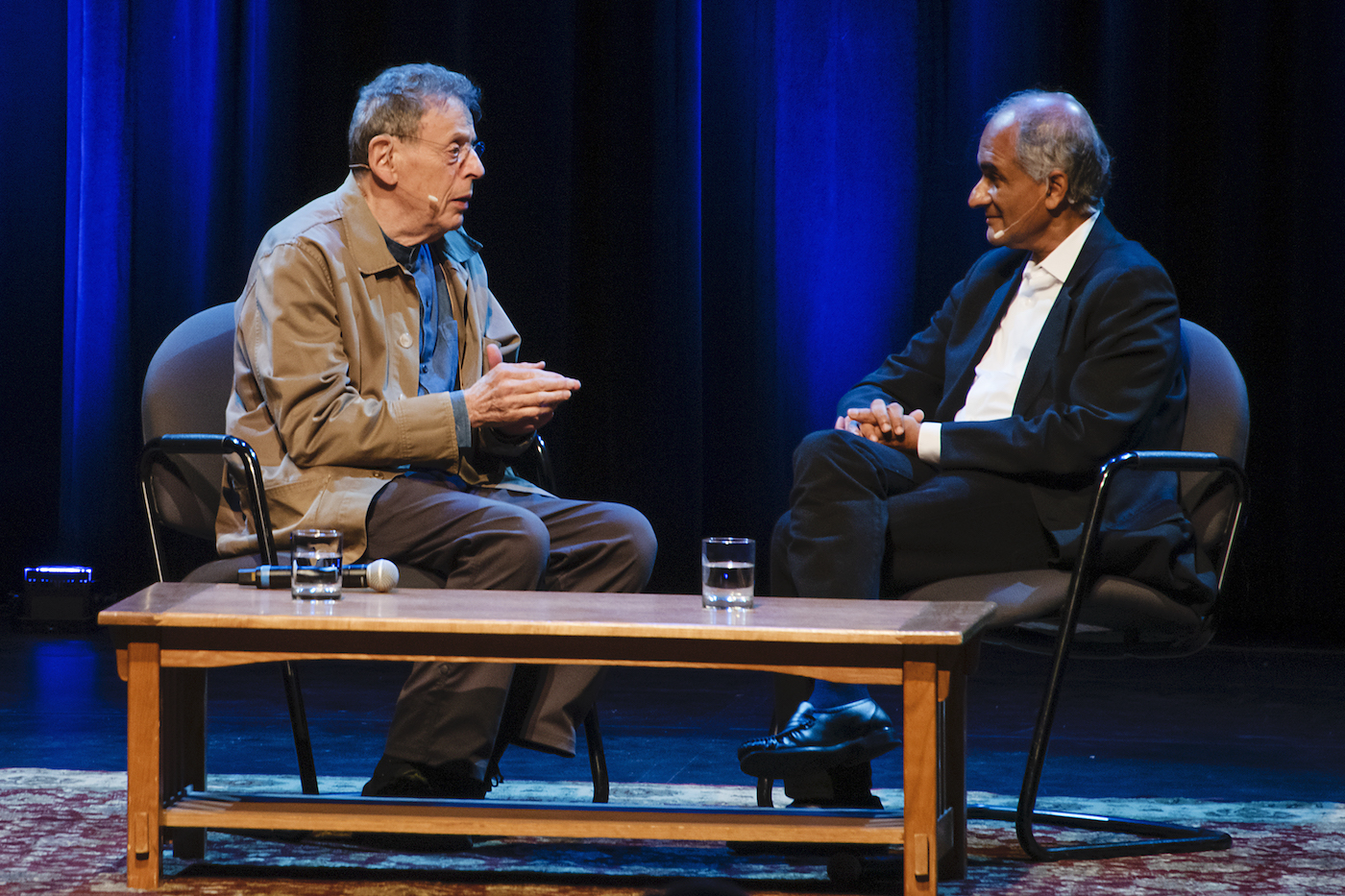

Philip Glass In Conversation with Pico Iyer

In a candid interview conducted by our town’s favorite literary author Pico Iyer, 82-year-old Philip Glass talked about his parents, becoming a musician-composer and still being stimulated by life to write and play the music he hears. The October 4 event was part of Pico’s talk series for UCSB Arts & Lectures, sponsored by Martha Gabbert, Dori and Chris Carter, Laura Shelburne, and Kevin O’Connor.

Glass stopped in our town on his way to his 19th season of “Philip Glass’ Days and Nights Festival in Big Sur” October 5, and the UK with his ensemble October 26-30.

Accolades abounded, but Glass maintained his compositional status, answering the questions Pico posed in his own unique language, cued with silences and phrasing and saying what he wanted when he wanted – just like his music. Much of what he reflected on in his early life can be found in his 2016 autobiography titled, Words Without Music: A Memoir. To the uninitiated, he is intangible; to musicians and artists he makes perfect sense of life in a changing world with realistic notes.

He of course was asked about being a NYC taxi driver and other sordid “day jobs” in 1970, but Glass did not flinch, “I looked forward to it. For most of us musicians, composers, choreographers, painters, and writers, there is no mechanism to jumpstart your career. My day job lasted till I was 40, quite frankly I liked it. In the ‘60s and ‘70s, you didn’t have to work all the time to pay rent, only three or four days per week. I didn’t believe I was suffering at all.”

He understood that he had to do as his parents asked, go to the college they wished, and when he was 18, with his own money and time, he took himself to NYC to study music at Juilliard, “I knew at age five I would do music and I wrote my first piece at fifteen. Artists are called, they are chosen, we don’t know by who, but it doesn’t matter, we just know.” He studied flute as a kid and listened in on his brother’s piano lessons.

His earliest influence was his father’s love of music. “Although he was not a musician and couldn’t read music, he owned a music store in Baltimore and I worked for him at age twelve. Every night he would come home with records and for hours listen to music, for him it was business, he had to find out why people purchased certain records and not others. I would listen with him and developed my ear for music. I thought that being a musician meant you would make money, because I was selling records at my dad’s store.”

Pico prompted, but Philip glossed over his studying with the legendary pedagogue Nadia Boulanger in Paris saying, “At that time I had two angels, one was fear and the other was love, you can guess who was who. From Paris I went across land to India, which you can’t do anymore, I was 28 or 30 years old. On that trip, I learned that music was a global affair. I am still meeting people whose music I don’t understand but if I listen long enough – like my dad did – I will and then we can play together. What attracts me most to a person is what I don’t know. It is important the way the world of music thinks about itself. For example, I met a group of people that had never traveled outside their village, but told me that they were nurturing and protecting their music for humanity.”

In 1957 he studied yoga. “We did not know what it was, so we looked it up under ‘y’ in the yellow pages to find a class! You know the Buddhists will say its karma and how can we argue with that? [jokes] I got my first grant at age 75. You ask, why are we here, and they say because we were here before!”

The rhetorical question that Glass shared he has had all his life is, “I always wondered where music comes from. In a strange way, artists are chosen, you can wrestle with it, but you can’t refuse it. Hard work is easier than creative work. Everything makes me tired except writing music. I began performing at age five, and it’s not difficult, it’s just another way of being with people. I don’t think about it. I now write about what I want to, isn’t that nice?! Yes, I get woken up in the night, and know that if I hear the music, it is a dream, so I get up, write it and play it. It’s a composite of energy you are a part of in that moment, a system of energy. There is a gift going on at that moment if you recognize it as such.”

In closing, Pico mentioned to Glass that his music is visceral.

Glass replied, “I know it can be seen that way because the music seems physical. The rules that define quality have abandoned us. This is a very rich time, not in money, but in arts we have never seen and music we can’t write down. The kids aren’t suffocated from the past. Same for me, I truly did not care what people thought. When the world is in its worst place, artistically it’s in its best place, and that’s happening right now. The 1950s was a terrible time, but the arts were there. At a time when society has lost its way, the arts seem to be showering us with intuition and beauty. It’s the way the energy works. I can statically prove it. I don’t have to be hopeful, it’s already there and I see it in children. I’m seeing it outside of me. We’re allowed to not know what we are doing. I write pieces now that surprise me. I used to work out of ideas, I am working out of intuition now. Ideas are interdependent, intuitions are gifts and they can be complete, like a poem with one syllable.”