Developing Inclusivity and Community Go Hand-in-Hand

Inclusion is not a special interest; it is a human right.

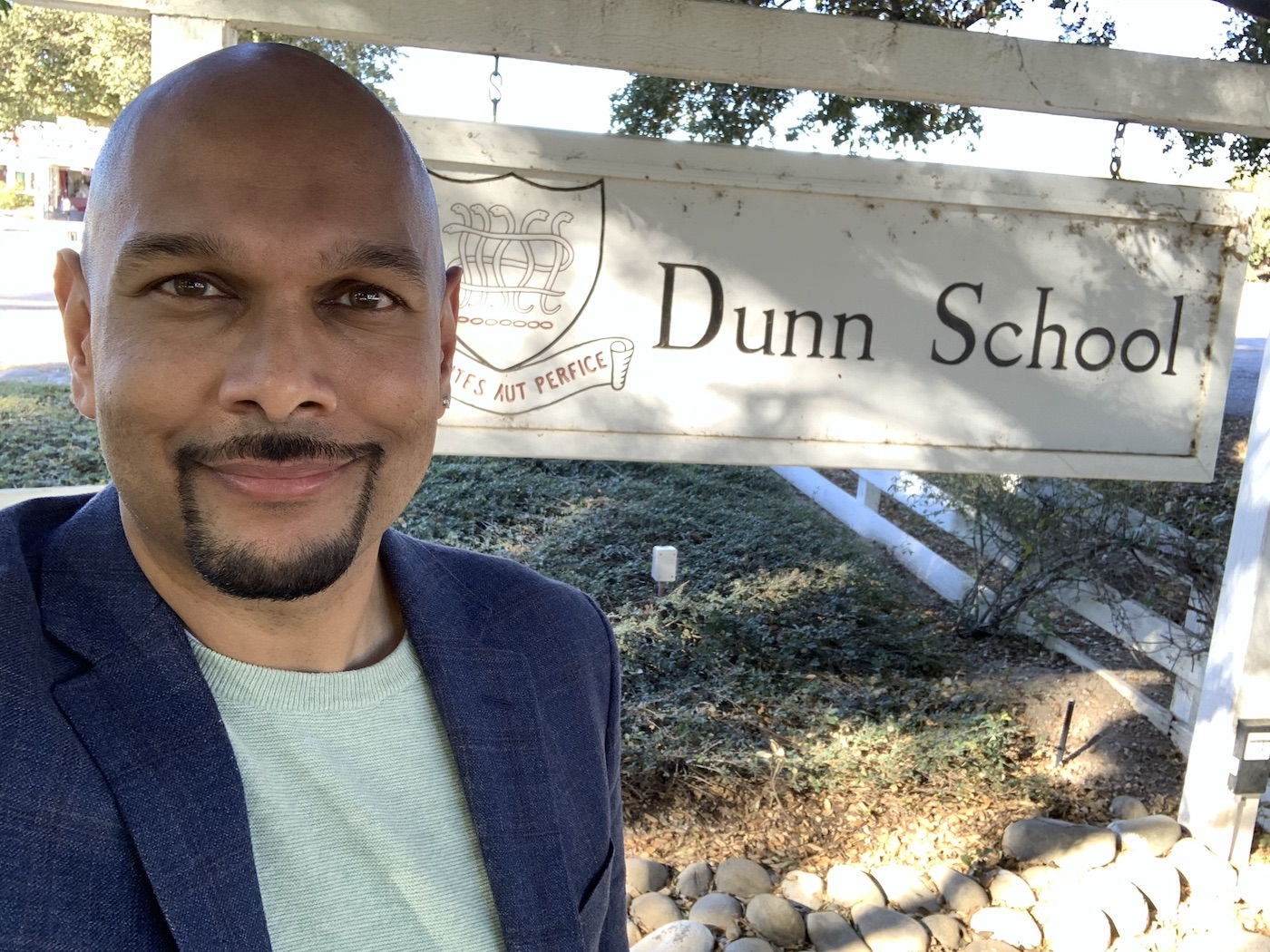

For the educator in me, this is a mantra that safeguards the term inclusion from how it trends currently in our discourse. In the rhetoric of our time, it has lost both its efficacy and meaning. It has become threadbare in its overuse and yet, from where I sit as the new Head of School at Dunn School, inclusion is a fundamental right that means every student is thriving because they are seen, heard, valued, and know that they belong.

In recent years, especially in education, Offices of Inclusion have proliferated in an attempt to turn the abstract promise of inclusion into an actionable human right, especially with regards to equity and full access to the promise of educational opportunities. I know, I’ve been a pioneer in this area. Now, I feel compelled to say they are no longer enough. At best they now epitomize a tokenistic rendition of inclusion to be used as a shield against critiques of ignorance and exclusion; and at worst they actively engage in the polarization of the very communities they were set up to heal.

We need inclusion now more than ever, as we suffer from an epistemological crisis in which ignorance manifested as prejudice and racism, reigns supreme. Cell phones have captured the vitriol and violence, and social media has given the world a glimpse of the sheer magnitude of the problem we face. Yet hope remains in education.

If education, both public and private, could come together to create a community-wide partnership on inclusion, generate programs that help students approach dialogue without embarrassment or guilt, and help each student they serve see each other fully as human beings, then we would matriculate students who are equipped to traverse the world as interculturally fluent builders of multicultural community, and thereby thrive.

So, yes, I believe education is the key, but I came by my faith in education the hard way.

Decades ago, while in law school, I half jogged across the slick floor, straight past the iconic statue of Martin Luther King, Jr., which greeted visitors to UC Davis’s King Hall. My mind was on the ride I was able to finagle from my friend Keenan at such a late hour, and I didn’t want to be late to meet him. My eyes were so weary after a long evening looking up terms in Black’s Law Dictionary and making tiny margin notes in my Civil Procedure reader that I didn’t see the dark silhouettes approaching me as I took my first rushed step outside the building.

I heard an audible click as their bright flashlights blinded me. I squinted hard and I was greeted with a gruff, “Who are you?” from the smaller, darker silhouette. Before I uttered a syllable, the larger figure beside it yelled with accusing aggression, “You’re not supposed to be here!” A crackle came from his bulky shoulder, “shhwwerp, do you have the suspect?”

“Who are you!?” asked his partner.

Still startled, I swallowed dry air, found some semblance of voice, and barely cracked out, “I-I-I’m a law student, I was just studying in the lib—.”

“Stop lying, who are you!?” They cut me off.

I instinctively reached towards the front right pocket of my green Adidas windbreaker to pull out my ID and keyset to King Hall hoping to prove to the interrogators that I really was a student. I stopped mid-motion when I was told to put my hands up. Paralyzed with fear, my body limply complied as I succumbed to the motions of my arrest. Ironically, as a UC Davis Law Student, I’d been asked to study the Miranda rights in my Criminal Law class, but I already had the words memorized from my lived experiences as a BIPOC man in America.

I sat terrified in the dank backseat of the squad car and ran through all the scenarios I’d become familiar with in my casebooks. I hadn’t done anything wrong — I had permission to study in the building. Why was I a suspect? I heard my arrestors utter phrases like “sexual assault,” “rape,” and the name of one of the residential dormitories nearby.

I began to understand as the officers spoke to dispatch that there had been an assault and that “I fit the description” of the culprit in their minds, or at the very least I did not fit their description of a law student. From the corner of my eye, I made out Keenan’s green Mitsubishi minivan driving slowly past the cop car, but it didn’t stop. The radio then crackled, “bzzsh… victim says it was a white male…”

When I heard those words, I fully exhaled, and remember the feeling of warmth returning to my cheeks. To this day, I still feel guilty for feeling relieved — after all, someone had been sexually assaulted on my campus. Ten minutes after the officers confirmed the information that came through, they finally let me go. I was a first-year student in Law School, and it was only my second week.

Education is Key to Solving Ignorance

There were many victims that night; there was the victim of the actual crime, me who was falsely accused; and the officers, who were so steeped in ignorance that they could not fathom a law student with dark flesh and features, because I fit another box entirely within the confines of their implicit bias.

This episode was not my first nor last run-in with law enforcement. Due to the color of my flesh, I have, like so many others, become conditioned to accept the normalcy of “fitting the description” in the minds of officers tasked to protect and serve. I’ve come to accept that in order to survive an encounter with the police I must comply even when compliance validates a misperception of who I am. Even, as we’ve seen far too many times, that compliance doesn’t guarantee my survival.

Yet, the way law enforcement has behaved with me doesn’t make policing the source of the problem, rather these examples are symptoms of a greater ignorance in the form of implicit bias, prejudice, and outright racism that pervades our society and makes all of us culpable, unless we actively counteract the hate with knowledge.

In law, working primarily in legal clinics, I found I could make a difference case by case, but as a teacher I saw that I could more directly counteract that ignorance: I could do so class by class, year after year. Ignorance was the ill-seed that kept our culture spiraling through a never-ending cycle of bigotry. Stereotypes were born, pre-judgements made, and fear gave way to violence over and over again. I knew that I was victimized by law enforcement my whole life because of the fear nurtured by ignorance spurred dangerous amygdalin responses in those charged to protect and serve. To root out that ignorance, I surmised, the solution lay in education.

As a public-school product I began there, in the classroom working with kids, setting up after-school interventions, trying to step away from the confines of state standards and STAR tests to do something meaningful with the kids assigned to my class. I was called to public charter schools soon thereafter and worked to build campuses and programs that were rich in multicultural coverage and appealed to the students most in need of attention. After a decade in the public-education trenches, battling a lack of funding and the ability to attract talent to the low pay, long hours, and endless bureaucratic headaches of teaching, I landed in the world of independent schools. These private schools were free of restrictive teaching standards and standardized testing, schools could offer financial aid to support the neediest students and had the means to compensate faculty fully.

Even all those advantages, though, weren’t enough to reach the goal of true inclusion.

I found that independent school programs at worst approached inclusion as an unattended third wheel to their Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) programs and at best as a special interest. DEI too often meant getting token representation in the door and then abandoning the kids who needed help navigating a world of affluence with only lint in their pockets. “Inclusion” focused on serving a special interest, leaving groups of students segregated and disconnected from each other.

I discovered that even the best practitioners of DEI were focused on preaching against the “isms” but did so in a manner that left the privileged students feeling bitter or guilty, and those less so, angry or ashamed. Calling out community members as a practice was in vogue, and a custom of inviting in, not so much. I was frustrated and at the end of my rope, but realized I had agency.

As a last-ditch salvo I applied to head the office of DEI at my progressive Bay Area school. I believed that I could steward a program that would build a truly inclusive community by facilitating the exchange of ideas, i.e., the knowledge we need about each other to stamp out the ignorance that is killing us. I got into education to work with both future police officers and the citizens they’d serve – but the methodologies I’d seen used thus far in the best DEI programs only polarized communities into the Black and White, as opposed to teaching students how to navigate the gradient of gray prevalent in the world in which we live.

I quickly realized that DEI was often a showpiece, to signify virtue rather than to get best outcomes. While admission numbers could measure “diversity” to some degree and equity could be defended by a budget line, inclusion relied on narratives that were hard to quantify and too easily dismissed by those who didn’t want to hear it.

Though it seemed improbable, I sought out to quantify inclusion, capture the narratives in data, so that school leadership could respond strategically and programmatically, ensuring that all students could thrive. I created the inclusion dashboard and my efforts gained notoriety and led to the creation of the Inclusion Dashboard Consortium, a partnership of more than 100 schools nationwide seeking to quantify inclusion.

Still, even I helped countless schools create their own dashboards, I sadly came to realize that many had begun using the fact they had the tool as sufficient evidence that inclusion existed. Sadly, a veil of ignorance descended, and school leadership could once again engage in cognitive dissonance towards the exclusion within their institutions. The inclusion dashboard had become a singular narrative, a story of progress, but a way to hide inequities that were prevalent within schools.

Therefore, a dashboard alone was not sufficient, a true collaboration between schools and a robust community of educators dedicated to inclusion was needed to ensure that inclusion doesn’t become a special interest. I realized that I was in the same fight I’d always been in and in order to truly make holistic and lasting change I needed to confront ignorance from a position of authority in a community that understood the whole student and had institutional capacity for inclusion.

Why Santa Barbara County?

I began looking for that school and saw the posting for Head of School at Dunn from a recruiter in my inbox. I opened it, took a glance and dismissed it: in my mind, Santa Barbara County was not diverse enough to pique my interest, and I let the recruiter know this. Then, my phone rang.

It was Guy Walker, a BIPOC Alumni and Dunn trustee, who exchanged brief introductions with me before speaking nonstop for nearly an hour. I was a rapt audience. He spoke to the potential for the community in the county, the role a school like Dunn could play by bringing international and West Coast diversity into its boarding program, he spoke to his profound experiences building community with the Chumash, the power of the Black and LatinX communities in the county, and the schools like Dunn thirsty to do this work.

Here was Dunn, a school where inclusion could be a human right and not a special interest, a secret in a valley that was hidden in a county that got very little attention compared to its neighbors in Northern and Southern California. There was an unpretentious quality to the school and the area, and I wondered at the potential for a network and real educational partnership in Santa Barbara County centered on inclusion.

During my interview I spoke to this potential for schools naturally disposed to competition setting aside their fervor for the interests of inclusion. I shared that when schools compete in the idea of “who is more inclusive,” they end up promoting exclusion — competition to appear more inclusive only equates to special interest-oriented programs whereby schools try to keep up with the Joneses, showcasing diversity to signify the virtue of inclusion, but in the end are just tokenizing students.

What I saw was the potential for a true partnership between schools, public and private, in Santa Barbara County, one that could easily be a model for the whole country.

“Imagine an inclusion consortium,” I said, “one that facilitate schools gathering and sharing data, resources, and best practices, while building better systems across our schools to support our students.”

The potential for such a thing requires two things: 1) the acknowledgment that inclusion is a human right and requires our full attention and 2) the ignorance that prevails if we do nothing victimizes us all.

At the end, I was asked if there was anything else I’d want the board to know about me, and I shared that it was important for me to connect with local law enforcement as I moved. A trustee asked for clarification and I shared as the first BIPOC Head of School in the area that introducing myself would help local law enforcement see me for who I was in the community and also establish a partnership to help work to protect and serve the safety of the school community I would lead.

The group realized that I was saying we had work to do together, and that the role of education cannot be confined to one school or one community. It is a partnership best facilitated and pushed by leadership that combats ignorance by building a diverse sense of community for everyone where inclusion is not a special interest, but a fundamental human right. I showed them that they were not searching for a Head of School, but, rather, for a community builder.

They smiled. After all, I fit the description.